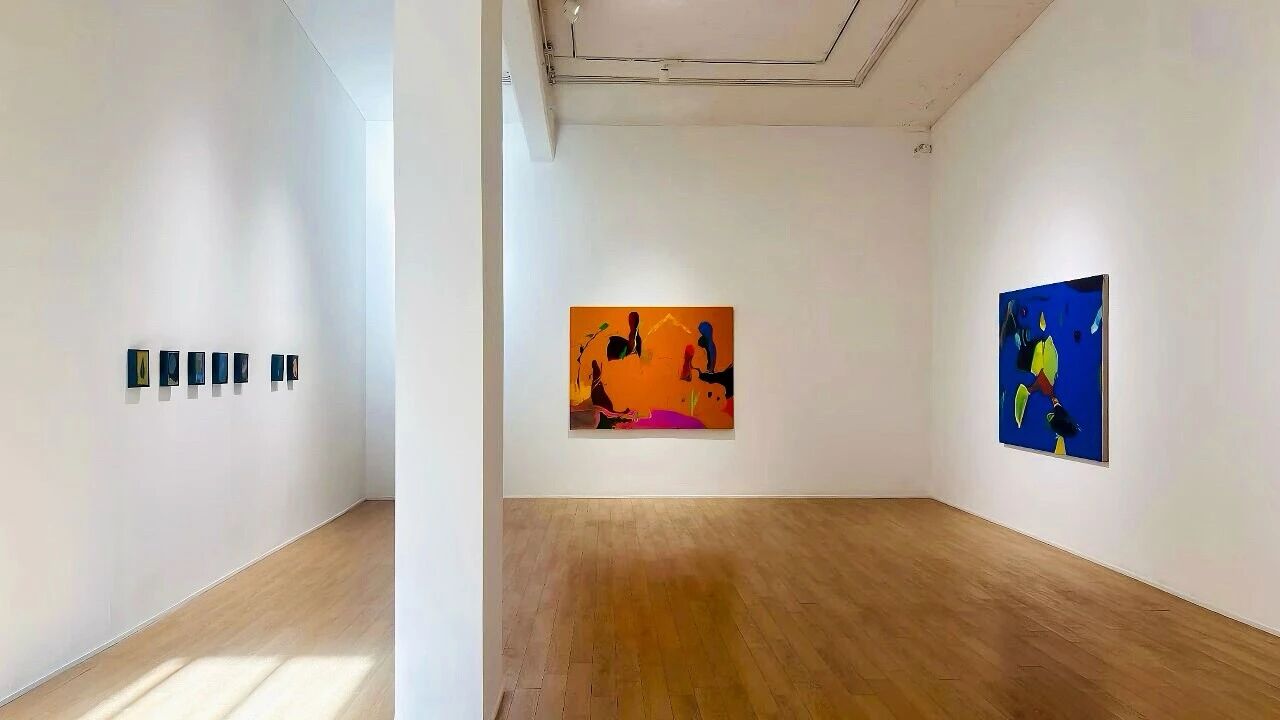

在画廊成立十周年之际,墨方荣幸呈现英国艺术家乔纳森·迈尔斯(Jonathan Miles)和中国艺术家许晨茜的双人展“当所有边锋都变柔和”。此篇为策展人邓婷与两位艺术家就本次展览而延伸的对谈。以下对谈中,“邓婷”简称“D”,“乔纳森·迈尔斯”简称“J”,“许晨茜”简称“X”。

1.数量成为形式

D:Jonathan,在你的《抽象1000》系列中,数量似乎是一个核心问题。观众常问:这一千件作品是否只是形式上的设定?当单件作品可能消隐于浩瀚整体时,是否仍有某种事物在重复中得以延续?

J:《抽象1000》提出了一个或一系列无解之问,实则是在探索表征之界的内外疆域,并在此过程中审视重复与差异的种种状态。作品本身构建了一种可能性:通过创作行为本身,或可建立起一种与风险暴露的关系——当意义及其消散在偶然性中相遇时,这种创作实践便成为了对隐匿于机遇元素中的消亡的直面。

D:我理解你这里的“重复”不是机械的,而是一种在做与消失之间的动态张力。晨茜,你的作品里也有类似的“生成—消散”节奏感,你会怎样回应?

X:我常常在画布上捕捉“呼吸感”,它既是重复的,也是瞬间性的。笔触和色晕像呼吸一样不断出现又消散,画面在不确定中延续。我想这与 Jonathan所说的“风险”很接近。我不是一个容易被安静吸引的人,可是在我的生命经验当中情感和直觉引领我见到过最震撼的“安静”的力量,因此我对它深信不疑。可我仍然常常处于躁动不安的状态下,在创作中我极力弥补,总是在一片混沌中艰难地找到一个栖息之所。最后有一些很轻的东西冲破重力浮现出来,我便完成了这一阶段的生命的使命。

甜与哀的密语, 布面丙烯,50×40cm,2025 许晨茜

Cipher of Sweetness and Sadness, Acrylic on canvas, 50×40cm, 2025 Xu Chenxi

2.抽象与再现

D:Jonathan,你提到抽象与再现之间的区分其实是一种虚假的两极。你认为真理是否存在于两者之外?

J:我认为再现与抽象之间的关系是一种虚假的两极,因为艺术作品常常逃避了界定这种差异的边界条件。因此,艺术在关于真与假的问题上总处于游移状态,它栖居在模糊与缺失之中,以此作为一种不确定性的存在方式。

D:我赞同这种“模糊性”。晨茜,你的作品既有透明的抽象,也保留某种身体性的痕迹。你怎么看待这种游移?

X:抽象的语言是隐晦的,画面中只留下某种痕迹或符号给观者,可是在这种凝练之中,唯一剩下的就是情感的强度,无论是平稳还是起伏,挣扎还是放弃,脆弱还是狂喜,都是某种变化,这种变化永无止境。我的潜意识里一定是暴露,可是画面并不一定真的这样做,它只是展现了这种不稳定和不确定以寻求继续下去。

无声的屈服,布面丙烯,40×30cm,2025 许晨茜

Silent Surrender, Acrylic on canvas, 40×30cm, 2025 Xu Chenxi

3.图像与绘画

D:我们来谈谈图像。Jonathan,你把“绘画的图像”与“图像的绘画”做了区分,并用“僧侣与囚犯”的比喻谈到时间。能否再展开?

J:僧侣与囚犯的区别是什么?囚犯被迫“服刑”,承受一段时间的流逝;而僧侣则试图吸收时间本身,使其流逝变得虚幻。画家可以被视为同时操练时间的流动与它的消失,并选择进入一种着迷的状态,从而退出时间的在场。贝克特就是这种姿态的例子,他让时间的意义连续性中止,因此被视为荒诞派作家。

D:晨茜作品中最初始的以及最核心的东西是什么呢?你如何理解绘画与时间的关系?

X:除了自然,还有什么是最初的开始呢?从脸开始我是没有意识的,没有计划的,它只是开始了,也自然地结束,驱使它的只有最简单的直觉。而吸引力是直觉的催化剂,能够产生疏离与亲密,这让我感到活着。我想我在绘画中潜意识地逃避时间所带来的重量,可是这些缓慢生成的结果又在回应时间所带来的美妙的沉淀,我总是觉得这些“极轻”的东西会积累出它的整体的智慧,时间自然地在其间流淌。

D:你的《快、更快、直到静止》是一个充满张力的标题。在你看来,绘画是否可以追赶意识,或者说,被意识“驱使”?它是动态还是静态的?

X:我觉得它并不能完全追赶意识,也不是随时受意识驱使,但它一定存在一种博弈,是一种中间状态,是充满想象力的空间。这个空间里画面不断生成,就像我现在在回答问题,我的脑海中不断地给出一个即时的答案,这种即时是片面的,也是充满张力的,它会走向力竭,也会留下深刻的痕迹。

快,更快,直到静止,布面油画,140×105cm,2023 许晨茜

Fast, Faster, until Still, Oil on canvas, 140×105cm, 2023 Xu Chenxi

4.文化与媒介的交融

D:Jonathan,你提到过东方艺术的影响并不在于表象,而在于感知方式。你从亚洲文化中汲取了哪些精神或哲学资源?这些资源又是如何影响你的艺术与文学实践的?

J:东方古典艺术的影响,与其说在于它的外观,不如说在于某位画家可能会将“脚”作为一种感知器官来使用,并与“眼睛”这一感知器官形成一种综合。在这种方式下,视觉与失明之间,或者更确切地说,感知与所见之间,建立起了一种关系。

J:你如何看待东西方的融合?

D:对我来说,东西方的融合并不是一种简单的拼接,而更像是一种“互为照镜”的过程。因为我自己曾在东西方的学习和生活之间不断往返:一方面,西方的艺术教育让我习惯于在逻辑框架与批判语境中理解作品;另一方面,我又始终被东方文化和哲思深深吸引,当我把这些经验带回到策展实践中,西方的理性与批判方法帮助我在策展中搭建清晰的叙事框架,而东方的感知方式则提醒我要留白,要让作品和观众之间有呼吸的空间。东西方的融合,在我这里更像是一种动态平衡。

D:晨茜,在你的创作中,电子屏幕、皮肤、纸张、画布之间的“媒介迁移”非常明显,这种不断转换是否是一种“寻找真正载体”的过程?

X:是的,它总是处在这种寻找之中,没有一种结果告诉我我已经找到了一个庇护所,也许他们组合起来才是某种朦胧的答案,这种答案又好像永远是朦胧的,这种情况下具体媒介的意义消失殆尽。

X:你觉得策展人和艺术家这两个身份的对你来说是怎样的关系?

D:对我来说,策展和艺术创作并不是分裂的两条道路,而是同一个关注方向的不同侧面。很多人会觉得策展是组织、规划和阐释,而艺术创作是表达和生成,但我更愿意把策展理解为一种艺术实践。当我在策展时,我并不只是安排作品与空间的关系,而是把整个展览当作一件可以“被体验”的作品来创作。空间的节奏、叙事的线索、观众的动线与情感体验,都是创作的一部分。空间对我来说就是另一种“画布”。在这块画布上,媒介变成了作品与观众,色彩与线条变成了叙事与空间,通过策展把不同艺术家的作品编织成一个共同的呼吸场域。

5.Lily O 与虚构

D:最后一个问题,Jonathan,你在构建虚构人物 Lily O 的时候,为什么选择让她“死亡”,而不是通过文本赋予她永生?

J:Lily O 的出现是一种意外,因为在叙事的开端并没有设计这样一个人物。但一旦她出现,她就被卷入了时间,于是死亡也就成为一种可能。当她死亡时,我开始流泪,因为她的死亡并不合乎逻辑,尽管它可能是一种必然。因为她在艺术与生活之间绘制出了一种生命。我借此找到了探索连续与断裂之间关系的一种方式。

D:这让我想到艺术的一个核心——虚构人物或形象的出现,总是同时带来创造与消逝。读到 Jonathan 的 Lily O 时,我感到她被不可逆的时间卷入——她的出现立刻使“终结”成为可能。这个瞬间启发了我去创造另一个人物:乌梦 ——名字来源于“乌有之梦”。乌梦不是 Lily 的复制,而是她在东方语境里的闺中知己;如果 Lily O 在“艺术与生命”之间拉出一条连续/不连续的张力,那么乌梦就尝试在“有/无”之间维持一条被呼吸撑起的细线:她不求不朽,而是练习可逝。

X:乌梦会创作什么样的作品呢?

D:我想她的绘画是透明而轻盈的,颜料层层叠加又被抹去,像呼吸一样进出,观众总是看到一个“正在消失的画面”。她还会在纸、屏幕、皮肤等不同载体之间迁移,用脆弱易逝的材料(墨迹、冰、蒸发的水痕)书写,让作品注定会淡去。晨茜,你会不会觉得,你画面里那些轻盈的瞬间,其实也有类似的命运?

X:是的。那些色晕、透明层次,其实也像 Lily O 和乌梦一样,带来一种转瞬即逝的生命。它们不是永恒的,却在消散中留下痕迹。

D:我很珍惜今天的对谈。Jonathan 带来的是关于“阈限、模糊与时间”的思考,晨茜则用“呼吸、透明与身体”回应这些命题。在我看来,你们的交汇点正在于:艺术既是生成,也是消失;是时间的重量,也是它的悬置。

丢失的档案-13,33×22cm,油画棒 纸本,2000 乔纳森·迈尔斯

The Lost Archive-13, Oil pastel on paper, 33×22cm, 2000 Jonathan Miles

On the occasion of its tenth anniversary, Mocube is pleased to present The Softening of All Edges, a dual exhibiton featuring British artist Jonathan Miles and Chinese artist Xu Chenxi. The following text is an extended conversation between curator Deng Ting and the two artists, offering further reflections on the themes of the exhibition. In the following interview, "Deng Ting" is abbreviated as "D," "Jonathan Miles" as "J" and "Xu Chenxi" as "X".

1. Quantity as Form

D: Jonathan, in your Abstract 1000 series, quantity seems to be a central issue. Audiences often ask: Are these thousand works merely a formal construct? When individual pieces might dissolve into the vast whole, is there something that still persists through repetition?

J: Abstract 1000 set up a question or a series of questions for which there is no answer rather there is an exploration of a threshold between the for and beyond of representation and within this an exploration of states of repetition and difference. The work itself sets up the possibility that the task of doing might yield a relationship to an exposure to what is at risk within the disappearance into the chance element embedded in such an encounter with meaning and its loss.

D: I understand that what you mean by “repetition” here is not mechanical, but rather a dynamic tension between doing and disappearing. Chenxi, your works also have a similar rhythm of “emergence–dissipation.” How would you respond?

X: I often try to capture a “sense of breath” on the canvas—it is both repetitive and instantaneous. Brushstrokes and color halos appear and vanish like breathing, and the picture continues in uncertainty. I think this is very close to what Jonathan calls “risk.” I am not someone who is easily drawn to stillness. Yet, in my life experience, emotion and intuition have led me to witness the most powerful force of “quiet,” and so I believe in it deeply. Still, I often find myself in a restless state. In creation, I strive to make up for this, always struggling to find a place of rest within the chaos. Finally, something light breaks through gravity and surfaces, and at that moment, I feel I have fulfilled this stage of life’s mission.

2. Abstraction and Representation

D: Jonathan, you mentioned that the distinction between abstraction and representation is in fact a false polarity. Do you think truth exists outside of the two?

J: I think of the relation between representation and abstraction as being a false polarity because work often evades the boundary condition which defines such a difference. Thus art is errancy in such matters of defining what is true or false, and resides in the conditions of ambiguity or loss as a mode of uncertainty.

D: I agree with this sense of “ambiguity.” Chenxi, your works contain transparent abstraction while also preserving traces of physicality. How do you see this shifting?

X: The language of abstraction is oblique—it leaves only certain traces or symbols for the viewer. Yet within this condensation, what remains is solely the intensity of emotion. Whether steady or fluctuating, struggling or surrendering, fragile or ecstatic, all are forms of change, and such change is endless. In my subconscious there is certainly exposure, but the canvas does not necessarily enact it literally; rather, it presents this instability and uncertainty in order to seek continuation.

3. Image and Painting

D: Let’s talk about the image. Jonathan, you’ve distinguished between “the image of painting” and “the painting of the image,” and you used the metaphor of the monk and the prisoner to speak about time. Could you elaborate further?

J:What is the difference between a monk and a prisoner? The prisoner is expected to do a stretch of time, whereas the monk attempts to absorb time itself by rendering its passage as illusory. Painters might be seen as exercising both time’s passage and its loss, and instead choose to be in a state of fascination as a form of withdrawal into the absence of time. Beckett is an example of such a posture—an arrest of time’s continuity of sense—and for this reason he has been framed as an absurd writer.

D: Chenxi, what is the most primordial, the most essential element in your work? And how do you understand the relation between painting and time?

X: Apart from nature, what else could be the very beginning? When I start with a face, it is unconscious, unplanned—it simply begins, and then naturally ends, driven only by the simplest intuition. Attraction is the catalyst of intuition; it generates both distance and intimacy, and that makes me feel alive. I think that in painting I subconsciously evade the weight that time imposes. Yet the results, slowly formed, in turn respond to the beautiful sedimentation that time brings. I always feel that these “extremely light” things accumulate into an overall wisdom, with time naturally flowing among them.

D: Your Faster, Still Faster, Until Stillness is a title full of tension. In your view, can painting chase after consciousness, or be “driven” by it? Is it dynamic or static?

X: I don’t think it can fully keep pace with consciousness, nor is it always driven by it. But there must be a kind of contest—a middle state, a space filled with imagination. Within this space, the image keeps coming into being, just as I am now answering your question: my mind keeps producing an immediate response. This immediacy is partial, yet full of tension; it can reach exhaustion, but it also leaves deep traces.

4.The Fusion of Culture and Medium

D: Jonathan, you once mentioned that the influence of Eastern art lies not in its appearance, but in its way of perception. What kinds of spiritual or philosophical resources have you drawn from Asian cultures? How have they influenced your artistic and literary practices?

J: The influence of Far Eastern Classical Art derives not so much from its appearance, but rather from the way a painter might use the feet as an organ of perception, creating a synthesis with the eyes as organs of perception. In this way, there emerges a relationship between vision and blindness, or more precisely, between what is sensed and what is seen.

J: What do you think about the merging of the West and the East?

D: For me, the fusion of East and West is not a simple patchwork, but rather a process of “mirroring each other.” I have personally moved back and forth between Eastern and Western contexts of study and life: on the one hand, Western art education has accustomed me to understanding works within logical frameworks and critical discourses; on the other hand, I have always been deeply drawn to Eastern culture and philosophy. When I bring these experiences into curatorial practice, the rationality and critical methods of the West help me construct a clear narrative framework, while the Eastern mode of perception reminds me to leave space, to allow breathing room between the work and the audience. The fusion of East and West, for me, is more like a dynamic balance.

D: Chenxi, in your work, the “migration of mediums” between electronic screens, skin, paper, and canvas is very apparent. Is this constant shifting a process of “searching for a true vessel”?

X: Yes, it is always in such a state of searching. No result has ever told me that I have already found a refuge. Perhaps their combination is a kind of hazy answer, and yet this answer seems to remain perpetually hazy. In such a condition, the significance of any specific medium all but disappears.

X: How do you see the relationship between the two identities of curator and artist for yourself?

D: For me, curation and artistic creation are not two separate paths, but different facets of the same concern. Many people think of curating as organization, planning, and interpretation, while artistic creation is expression and generation. But I prefer to understand curation as a form of artistic practice. When I curate, I am not merely arranging the relationship between works and space, but treating the entire exhibition as a work that can be “experienced.” The rhythm of the space, the threads of narrative, the movements and emotional experiences of the audience—all of these are part of the creation. For me, space is another kind of “canvas.” On this canvas, the medium becomes the works and the audience, colors and lines transform into narrative and space, and through curating, the works of different artists are woven into a shared field of breathing.

5. Lily O and Fiction

D: One last question, Jonathan: when you created the fictional character Lily O, why did you choose to let her “die,” rather than granting her immortality through the text?

J: Lily O emerged as a surprise, because there was no design of such a figure at the beginning of the narrative. But once she appeared, she was implicated in time, and so death became a possibility. When her death occurred, I began to shed tears, because her death was not logical, even though it might have been a necessity—since she had drawn a life between art and life. Through this, I had given rise to a way of figuring the relationship between continuity and discontinuity.

D: This makes me think of a core of art—the emergence of fictional figures or images always brings both creation and disappearance. When I read Jonathan’s Lily O, I felt that she was swept into irreversible time—her very appearance immediately made an “ending” possible. That moment inspired me to create another figure: Wu Meng—a name derived from the phrase “the dream of nothingness.” Wu Meng is not a replica of Lily, but her intimate confidante within an Eastern context. If Lily O stretched out a tension between continuity and discontinuity, between art and life, then Wu Meng tries to sustain, like a thread upheld by breath, the tension between being and non-being: she does not seek immortality, but rather practices perishability.

X: What kind of works would Wu Meng create?

D: I imagine her paintings would be transparent and weightless, with layers of pigment applied and erased, ebbing and flowing like breath, so that viewers always see an “image in the process of vanishing.” She would also migrate across different carriers—paper, screens, skin—writing with fragile, perishable materials (ink traces, ice, evaporating water marks), so that her works are destined to fade. Chenxi, don’t you think that the fleeting moments in your images share a similar fate?

X: Yes. Those color halos, those transparent layers, are actually like Lily O and Wu Meng—they bring a kind of fleeting life. They are not eternal, yet in their dispersal they leave behind traces.

D: I truly cherish today’s conversation. Jonathan has brought reflections on “threshold, ambiguity, and time,” while Chenxi has responded to these themes with “breath, transparency, and the body.” To me, your intersection lies in this: art is both emergence and disappearance; it is the weight of time, and also its suspension.

关于艺术家

乔纳森·迈尔斯(Jonathan Miles),英国艺术家、讲师、作家及策展人,现居伦敦,并在皇家艺术学院任教。他于1969年至1973年就读于斯莱德艺术学院(Slade School of Art),并于1980年代初担任《ZG》杂志伦敦版编辑。他的跨学科实践涵盖绘画、虚构写作与批判理论,常通过将文本与图像并置,引发二者的对话,从而打破固有意义与叙事结构。

Artist Bio

Jonathan Miles is a British artist, lecturer, writer, and curator based in London, where he teaches at the Royal College of Art. He studied at the Slade School of Art from 1969 to 1973 and served as London Editor of ZG Magazine in the early 1980s. His multidisciplinary practice spans painting, fiction, and critical theory, often bringing text and image into dialogue to disrupt fixed meaning and narrative structure.

关于艺术家

许晨茜是一位多领域发展的艺术家,2015年毕业于中央美术学院获学士学位,2018年毕业于英国皇家艺术学院获硕士学位。她的实践涵盖绘画、珐琅艺术和行为艺术等,专注于颜色、形态、情绪、连贯性以及作品题词的表达,始终将直觉的力量置于首位,在形式与媒介的自由探索中寻求突破。

Artist Bio

Xu Chenxi is a multidisciplinary artist who earned her Bachelor's degree from the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in 2015 and her Master's degree from the Royal College of Art (RCA) in 2018. Her practice spans painting, enamel art, and performance, with a focus on color, form, emotion, coherence, and the expressive potential of textual inscriptions in her works. At the core of her creative process lies an unwavering emphasis on the power of intuition, pursued through unrestrained experimentation with form and medium.

关于策展人

邓婷(Deng Ting), 独立策展人,艺术家,现任RET艺术执行董事。其毕业于美国加州大学欧文分校和英国伦敦皇家艺术学院,并进修于苏富比艺术学院。她作为UCCA青年赞助人委员与当代艺术实践小组组长、MACA先锋赞助人,持续发挥年轻先锋的力量。主要关注女性创作以及人类学视角下的死亡、仪式与神秘主义,并且将策展、书写、收藏作为一种艺术创作和研究方式,曾创立了「无空间No Space」和「O Collection+Projects阴性收藏计划」。

Curator Bio

Deng Ting is an independent curator and artist, currently serving as the Executive Director of RET Art. She holds degrees from the University of California, Irvine, and the Royal College of Art in London, and has also pursued further studies at Sotheby's Institute of Art. As a member of the UCCA Young Patrons Committee and leader of its Contemporary Art Practice Group, as well as a Pioneer Patron of MACA, Ting continues to play an active role as a young and progressive force in the contemporary art scene. Her curatorial and research interests focus on female artistic practices, and on themes such as death, ritual, and mysticism from an anthropological perspective. She approaches curating, writing, and collecting as integral forms of artistic creation and critical inquiry as the founder of No Space and the O Collection + Projects: Feminine Collection Initiative.

©文章版权归属原创作者,如有侵权请后台联系