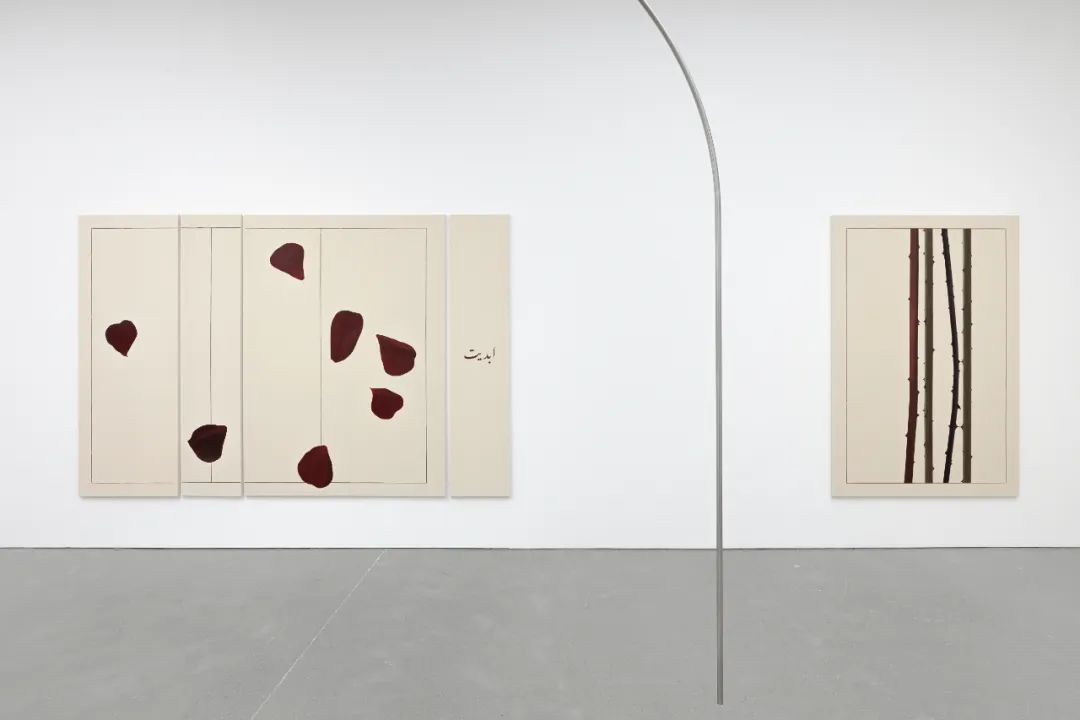

韩梦云“无尽的玫瑰”展览现场,香格纳上海,2023。

摄影:凌卫政,图片来源:艺术家韩梦云及香格纳画廊 ©韩梦云

韩梦云的实践回应着欧亚跨文化混融现象的去殖民化问题,这种混杂交融发生于广阔的时空地景之上,脱离了源自西方观念凝视的主导性调介。她在艺术生涯初期接受的是西方传统下的油画训练,但随后则从艺术创作的单一视角转向了欧亚大陆今时往昔深远的跨文化语境下历史连结的复杂性。

交叉性以及帝国主义的历史遗留是她实践中另一种反复出现的重要修辞。通过她身为女性下庶群体一员的自身体验,以及在争取可见性、争取塑造行星文化话语的平等机会中关于他异性“团结”高原效应的新兴概念,她调介着个体与集体的关系。韩梦云受《ArtAsiaPacific》委托撰文,其英文原文《One on One: Han Mengyun on Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak》(韩梦云谈斯皮瓦克)发表第134刊。其中艺术家谈印度文学理论家以及批评家斯皮瓦克关于属下身份、第三世界女性创作者的困境以及翻译的不可能性等议题,以回应影响其创作概念和艺术实践的多元思考。

韩梦云谈斯皮瓦克

作者:韩梦云

中译:吴析芸

为追溯有关镇压的历史和揭露让「属下阶层(subaltern)」女性噤声的权力机制,比较文学学者斯皮瓦克在其论文《属下能说话吗?》中引用了英国在1928年对印度「娑提(sati)」习俗的废除和罪犯化。「娑提」指一种让印度教寡妇在其亡夫火葬堆中自焚的仪式。利用德里达的解构主义,斯皮瓦克认出了在缺少女性意识心声之下隐藏着的两个谎言:英国人口中「白人男性从棕色男性手中拯救棕色女性」那帝国主义的征服性言论,印度本土主义者口中「那些女人事实上愿意去死」的看法——对他们来说,娑提是他们效忠以传统作为反动意识形态的重要证明,和对于其丧失本源的一种怀念。正如斯皮瓦克解释道:「在父权制和帝国主义之间……女性的形象消失了,并不是消失在原始的虚无中,而是消失于暴力的穿梭之中,这是夹在传统和现代化之间的『第三世界女性』的被置换的、流离的形象。」

我凝视着属下女性身处的深渊,看见的不过是一种极度清晰的黑暗与寂静。如临床诊断一般,这些长期感受到的、被忽视的、忍受着的、但却又未被历史承认的病症在此刻炙热地觉醒。我精通的父语和外来语却不曾对我开口;我质疑归属的可能性。我任何尝试出口的声音都会在语言、地方、身体里、于那些不可名状的空隙中、暴烈地结束。不存是绝症,属下皆无言。

我不愿为了博得文化流动性而去宣称自己作为一个第三世界知识女性的属下身份。但斯皮瓦克所提供的理论工具的确有助于理解第三世界属下女性的困境和其在文化讨论中的缺失,且有助拷问了在被父权制,殖民主义,帝国主义,和全球化所共谋的语境中(自我)表征的权力机制与困难。这种语境也构建了我身上被他人所构建的内部声音。作为一个投身全球艺术舞台的中国女性艺术家,在思考我为何必须尊重发声的自主性、而非沦为暴力表征下或是甜蜜地自我东方化的牺牲品时,这种意识变得更加重要。但这种自保远远不够,「女性必须要讲述彼此的故事。」

斯皮瓦克的翻译政治建基于她对属下女性的关注,也是我目前视艺实践的政治基础。斯皮瓦克宣称:「翻译是不可能但必要的。」生长于中国经济改革时期,我深深体会到了语言间不可逾越的存在差异。尽管我所接受的多语言教育丰富了我对世界文化多样性的理解,但它同时也为我建立了一座把我割裂的巴别塔。我关乎性别的经历进一步加剧了这种意译的艰难。那被多语杂音和被灭声的女性身份所分割至精神分裂的存在是我理解那“不可能性”的基础。归根结底,翻译这种行为是在一个不承认她的世界中构建这个「他者」。承认这种可能性等同于粗暴地否认与「她(他)者」在存在上的差异,因此,尤其是在单语主义和西方化在全球范围内膨胀的今天,翻译是不可能但绝对必要的。

对我而言,绘画也是语言。每种绘画传统都与令其构成符号和特殊性的文化背景和语言密切相关。在欧洲和战后美国现代主义传统的长期主导下,架上油画已经成为了人们想到绘画的直接反应——但「画」、「نگارگری ایرانی 」、「चित्र」 以及更多,与它们各自相映的认知论,又是什么呢?当其多元性被同质化时,我们这个已经全球化的艺术世界只会说更少的语言。在双重束缚中的另一面,女性也总是被画和为之而画。

翻译不可能创造一个公正的世界或是构建异文化之间的平等。尽管,也正是因为如此,我们更必须去翻译——为了自己和其他女性——那些被双重奴役至消失的属下女性必须在意识到双重束缚和暴力转码的风险下塑造属于自己的形象。我艺术实践中的行动主义,是为了承认文化之间的差异,通过语言学习为了找回、修复那些遗失和损坏的认知论,并补充女性和她们个体差异间被迫缺席和沉默的地方。

译者的任务,对于斯皮瓦克来说「是促进原作与它的影子之间的一种爱,一种容许破损的爱。」它接受了这种因差异间必然的冲突的所造成的磨损,我因而觉得这种爱格外令人感动。跨越所有的边界,作为一个女性主义译者与艺术家,我的职责是去促进这种爱,建立一个作为全球多样性的灯塔的巴别塔,成为属下的回声,并欢迎女性去享受世界语言及图像的硕果,这是她们自己的遗产。

注:本文选自原载于《ArtAsiaPacific》7/8月第134刊的英文原文《One on One: Han Mengyun on Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak》(韩梦云谈斯皮瓦克)。有关艺术家写作实践的详情可于其个人写作网站上查阅:www.limitedviews.org

Han Mengyun’s practice aims to address the decolonisation of the phenomena of Eurasian transcultural hybridisations that occurred across vast landscapes of time and space from the dominative mediation of the Western conceptual gaze. She was initially trained in the Western tradition of oil painting but diverted from the singular viewpoint of art production towards the complexity of historical ties in the profoundly intercultural context of the continent’s history and present.

The subjects of intersectionality and the legacies of imperialism are another significant recurring trope in her practice. Weaving the personal and collective experiences of the female subaltern into an alternative space of solidarity, she engages with the struggle for visibility of the subaltern and for their equal access in shaping planetary cultural discourse. Commissioned by ArtAsiaPacific this year for Issue 134, Han Mengyun discusses the Indian literary theorist and critic Gayatri Spivak’s influence on her artistic practice and her feminist awakening enabled by Spivak’s seminal essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?”, as well as contemplation on the subaltern struggle, third world female artists in a creative double bind and the impossibility of translation, in article “One on One: Han Mengyun on Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.”

Han Mengyun on Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Author: Han Mengyun

To trace the history of repression and reveal the mechanisms of power that silence the subaltern woman in “Can the Subaltern Speak?” (1988), comparative literature scholar Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak drew on the example of the English abolition and criminalization in 1829 of sati, the Hindu rite of self-immolation of a widow upon her deceased husband’s funeral pyre. Using Derridean deconstruction, Spivak identifies two lies in the absence of the woman’s voice-consciousness: “White men are saving brown women from brown men” by the British as imperial rhetoric of subjugation; and “The women actually wanted to die” by the Indian nativists, for whom sati was an important proof of their allegiance to tradition as a reactionary ideology and of a nostalgia for lost origins. In Spivak’s words: “Between patriarchy and imperialism . . . the figure of the woman disappears, not into a pristine nothingness, but into a violent shuttling which is the displaced figuration of the ‘third-world woman’ caught between tradition and modernization.”

Gazing into the abyss where subaltern women dwell, I saw darkness and silence in their utmost clarity. A moment of searing awakening, akin to the clinical experience of diagnosis, of symptoms long felt, neglected, and endured, but never acknowledged, for they have no record in history. The father and the alien tongues that I speak yet do not speak me; I question the possibility of belonging. Any attempt to utter ends up in a violent shuttle into the unnamable gaps of languages, places, and bodies. The illness of absence is terminal—the subaltern cannot speak.

I do not wish to claim subalternity in my position as a Third World intellectual woman with access to cultural mobility. But the understanding of the Third World female subaltern’s predicament and women’s perennial absence in cultural discourse, via the theoretical tools provided by Spivak, proved incredibly helpful to interrogate the mechanisms and problematics of (self-)representation in the complicity with patriarchy, colonialism, imperialism, and globalization, which construct the interior voice(s) spoken by the other(s) in me. This awareness is ever more critical in thinking about the ways in which I must honor my agency to speak, as a female artist from China participating in the global art arena, without falling prey to the violence of representation and to the sweetness of self-orientalization. But self-preservation is not enough and “women must tell each other’s stories.”

Spivak’s politics of translation, rooted in her concern with subaltern women, is the foundation of the politics of my current visual practice. Spivak claims that “translation is necessary but impossible.” That insuperable difference of existence between languages is what I experienced deeply growing up during the economic reform in China. While my multilingual education enriched me with understanding of the diversity of world cultures, it has also built a Tower of Babel that fissures me. My gendered experience further compounds the difficulty beyond literality. This schizophrenic existence fragmented by multilingual cacophony and silenced womanhood is the basis of my understanding of that impossibility. Ultimately, to translate means to construct the Other in a world that does not recognize her. To assume such possibility is to violently deny the Other’s difference, which is exactly what makes translation impossible but also necessary, as monolingualism and Westernization expand globally.

To me, painting is also language. Each painting tradition is intimately connected to the culture and language that forge its specificity and semiosis. Under the continuing dominance of the European and postwar American modernist tradition, when one thinks of painting today, “oil-on-canvas” comes to mind. But what about 畫, نگارگری ایرانی , चित्र, and beyond, along with their respective episteme? Our globalized art world speaks less languages as multiplicity is homogenized. On the other side of the double bind, women have always been painted and painted for.

Despite, and because of, the impossibility of translation to make a just world and to instate the parity of cultures, we must translate. For the subaltern women who are double subjugated into disappearance, women—for themselves and for other women—must make their own image, with the awareness of the risk of the double bind and violent transcoding. The activism in my art practice is to recognize the difference between cultures, to retrieve and repair lost and damaged episteme by learning languages, and to supplement where women and their individual differences are made absent and silent. “The task of the translator,” says Spivak, “is to facilitate this love between the original and its shadow, a love that permits fraying.” I find this love extraordinarily moving for it embraces fraying as a result of inevitable conflict between difference. By transgressing all borders, my task as a feminist translator-artist is to foster this kind of love, to build a Tower of Babel as a lighthouse of global diversity to be the echo of the subaltern, and to welcome women to enjoy the wealth of world languages and images as their own legacy.

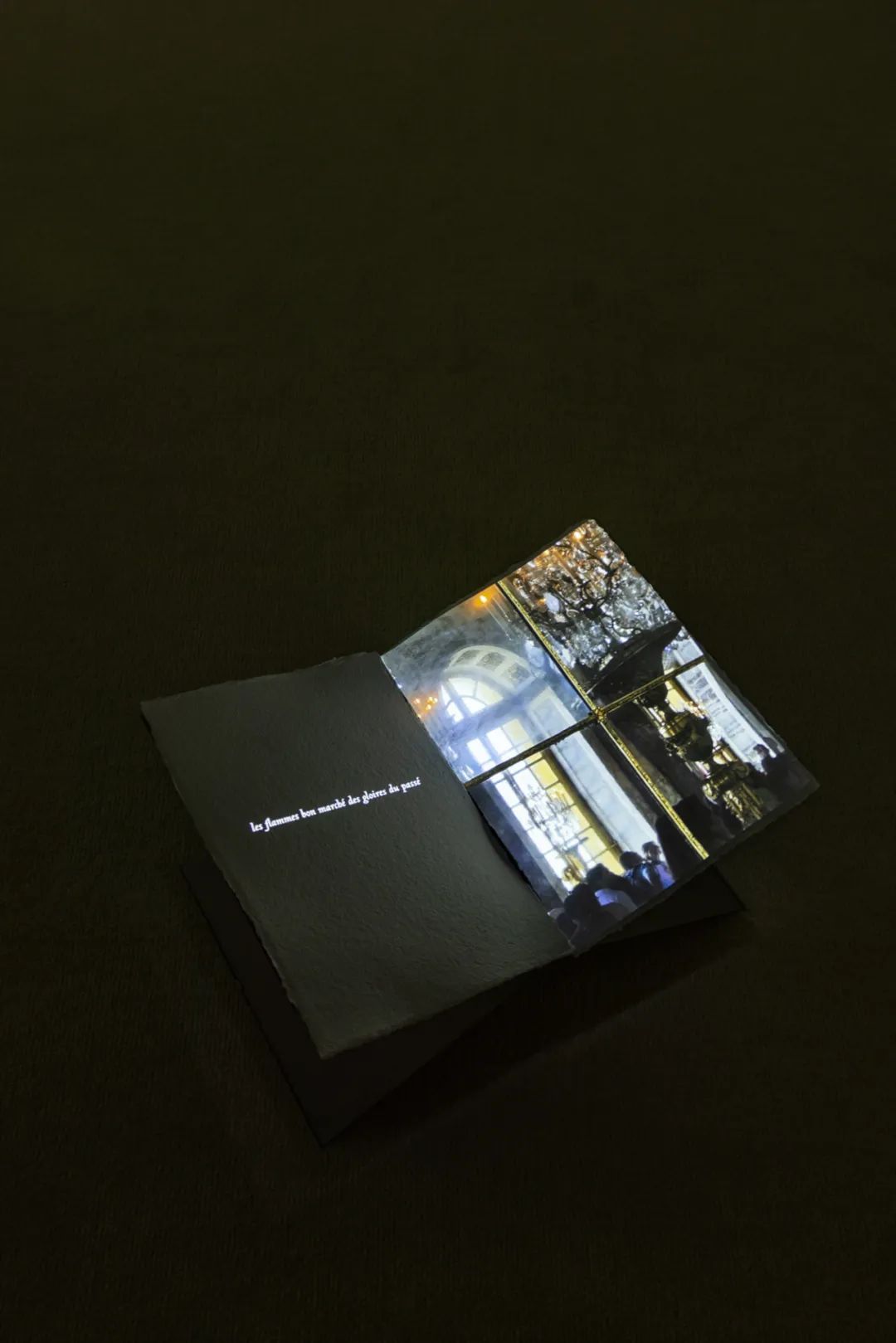

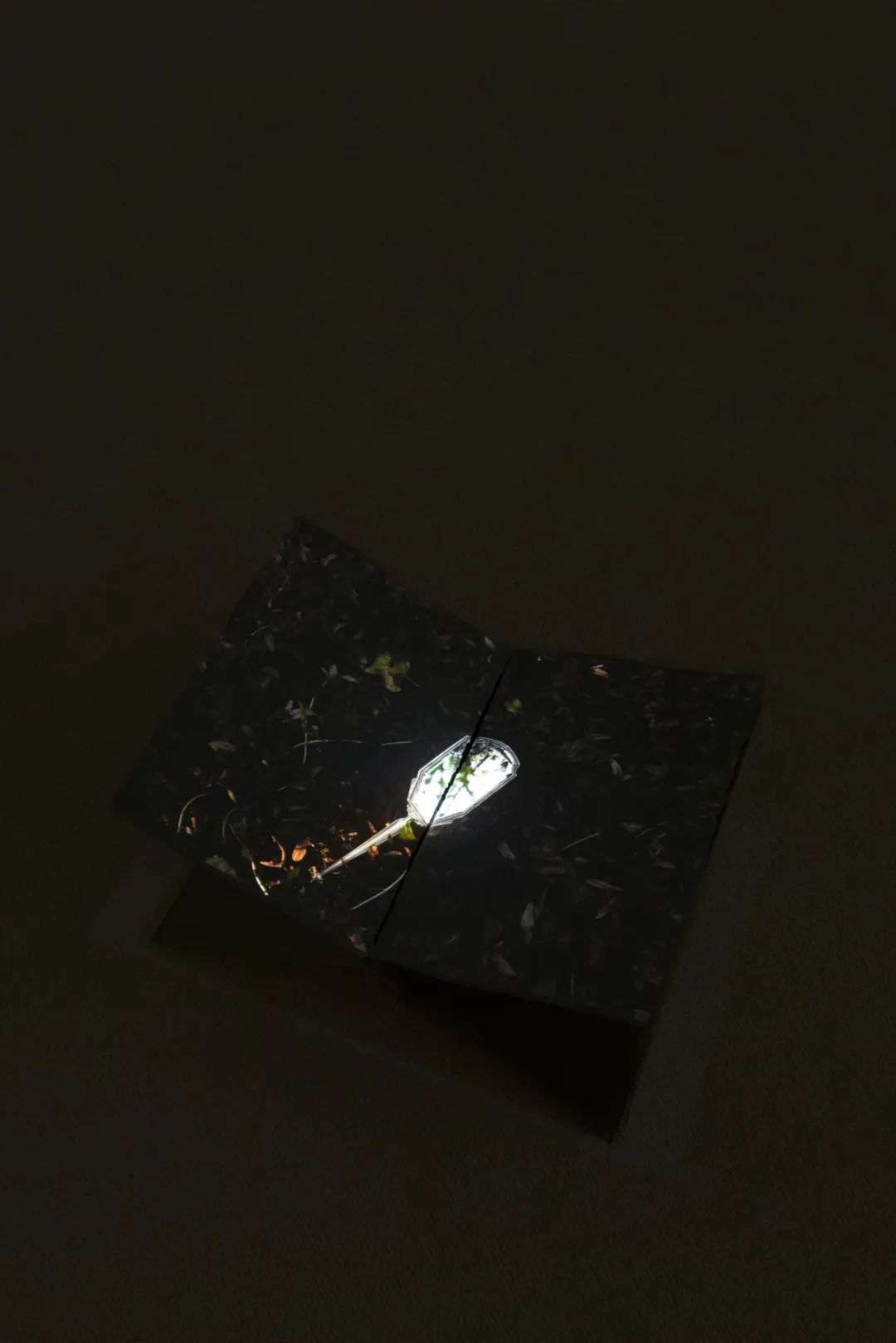

韩梦云《五卷书:太初之时, 梦, 书,月的礼赞,欲望》,2023,五屏彩色、无声、循环播放影像装置,艺术家定制不锈钢书立,印度 Khadi 手工纸

Note: One on One: Han Mengyun on Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak was originally published by ArtAsiaPacific in Jul/Aug Issue 134. For more information about the artist’s writing practice, please visit Han Mengyun’s writing website: www.limitedviews.org

©文章版权归属原创作者,如有侵权请后台联系