▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

翟倞个展:日常生活的颂歌

在法国作家茨维坦·托多罗夫(Tzvetan Todorov)的著作《日常生活颂歌》(Éloge du quotidien)中,日常被赋予了一种超越琐碎的意义。他指出,真正的存在经验未必依赖于宏大的历史叙事、激烈的政治斗争或崇高的理想,反而更常栖身于微不足道的生活片段中。这一观点促使我们重新审视日常,它并不等于庸常的重复,而是一种潜藏的力量,构成人类生活的基石。

正因如此,相较于宏大的史诗再现,“日常”在艺术史中长期于边缘与中心之间摇摆。荷兰黄金时代的风俗画与静物画,通过对生活片段的专注凝视,让“日常”在艺术的表达中庄严化,现代主义绘画则常将日常经验转化为形式探索的素材。及至当代语境,它不仅仅是生活的再现,更演变为一种观念的生成方式。翟倞的展览“日常生活的颂歌”正是在这一背景下展开:他通过近期的绘画实践,将个人经验、虚构叙事、寓言性意象与艺术史传统交织,为日常的层次中,寻找值得“歌颂”的意义。

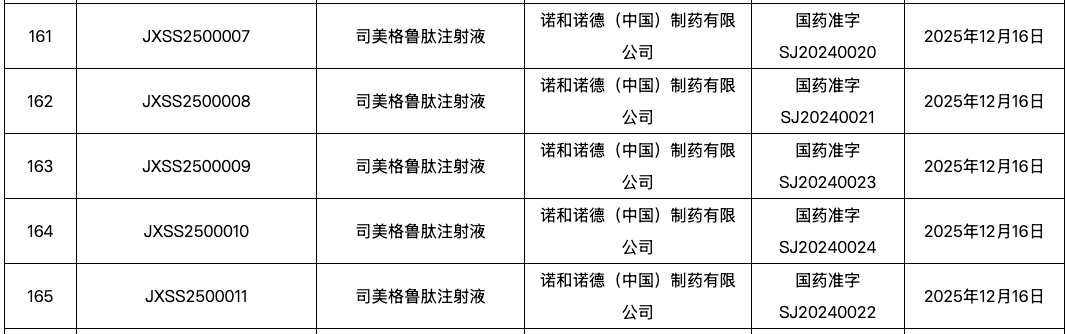

▲翟倞,要是有一种醉是因为知识而醉就好了,布面油画,235 × 210 cm,2025 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, How wonderful it would be to be intoxicated on knowledge, Oil on canvas, 235 × 210 cm, 2025 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

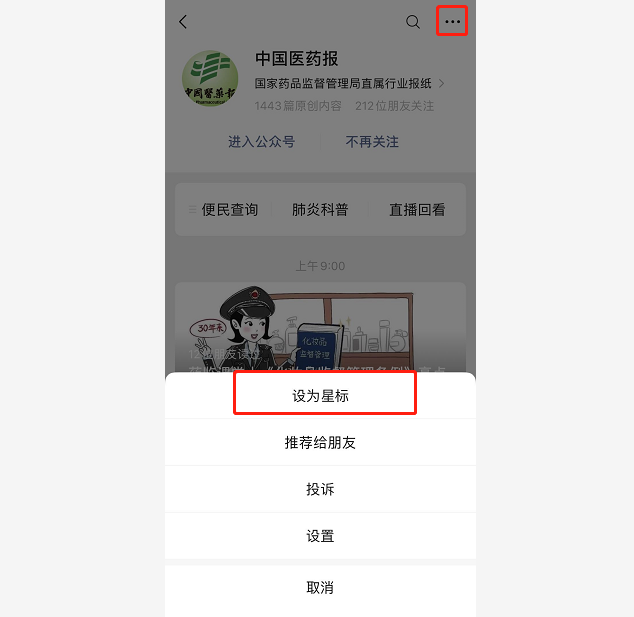

步入千高原艺术空间的一层展厅,《要是有一种醉是因为知识而醉就好了》,《一个有魅力的人》,以及那只被高高架设在喜七设计的阶梯般支架上的、神情惊悚的猫,共同传递出一个明确的信息:翟倞的绘画无意于构建完整的事件叙述,而是致力于对瞬间的捕捉,并挖掘其背后潜在的叙事强度。

▲翟倞,一个有魅力的人,布面油画,60 × 50 cm,2024 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, A charming person, Oil on canvas, 60 × 50 cm, 2024 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

翟倞的作品沿袭了艺术史脉络中的开放和复杂。他既吸收毕加索、安格尔的形式经验,也关注基彭伯格式的戏仿策略,以此反思自身如何在传统与现代之间寻找位置。同时,他他大量地阅读(从桑塔格到媒介学)与观影,将理论思想与影像场景转化为绘画的叙事单元与内在节奏。正是这种跨学科的叙事机制,促成了他创作方向的演进:早期作品中相对直白的政治性表达,逐渐让位于对日常的微观叙事。然而,宏大议题并未消失,而是如盐溶于水般,通过具体的细节与个体经验间接地显现出来。私人的场景与广阔的社会逻辑在画布上叠合,使作品超越了简单的立场宣言,呈现出多重解读的复杂结构。

在近年的创作中,他愈发在意画中人物那些转瞬即逝的姿态与眼神,会沿着目光流转间的路径去捕捉眼神的落点、动作的中途、未完成的状态,并以此作为构建叙事的关键。他的画面不依赖堆叠过多的道具或符号来丰满叙事,而以扑面而来的构图让观者能够近距离地辨识人物的肢体或手臂如何抵至画布的边缘,仿佛场景本身便可延伸到我们所处的现实空间。与古典绘画保持审慎距离的秩序感不同,这种处理方式将观者直接拉入画面的场域。荷兰风俗画家维米尔(Jan Vermeer)、彼得·德·霍赫(Pieter de Hooch)等人在作品中曾运用过相似的叙事策略,无论是女子倒牛奶、孩子嬉戏还是士兵饮酒,他们捕捉平凡的日常瞬间来营造亲近感。而翟倞的独特之处在于,他更强调动作与目光本身蕴含的叙事强度,其目标已超越了场景的再现。他在延续荷兰画派即时性的同时,更进一步地将“观看”本身凸显为重要的经验过程。

▲翟倞,有朋自远方来,布面油画,40 × 50 cm,2025 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, It is great pleasure to have friends come afar, Oil on canvas, 40 × 50 cm, 2025 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

翟倞所呈现的这种经验往往来自记忆与虚构的交织。《有朋自远方来》就取材于艺术家在北戴河沙滩上的一次真实经历:醉酒后与朋友在夜晚遇见成群的小螃蟹。它们以肖像的方式描绘为陌生化的存在,仿佛来自外星的访客。标题借用《论语》中的经典语句,却将“远方来客”的指涉从人转向了自然界的微小生物,使一段个人回忆变为寓言式的叙事。类似的转化逻辑也体现在《把海水喝干》中。画面将醉酒的姿态、海水的意象与灌注的动作结合起来,酒瓶在其中与观音净瓶形成呼应:一个象征世俗的消耗与失控,另一个承载宗教的赐予与慈悲。二者在画面中重叠,使日常器物获得象征意义,让宗教意象落入凡俗的日常。

“酒”的经验如一条草蛇灰线,贯穿了整个展览,呕吐、狂舞、失态的身体姿态,构成了基本的叙事单元。《要是有一种醉是因为知识而醉就好了》直接描绘醉酒后的瞬间,而其标题则暗示了另一种可能:倘若醉意来自知识的充盈而非酒精的麻醉,生活将被怎样重塑?这一假设深植于翟倞广泛的阅读谱系,他长期涉猎哲学、文学与媒介、理论,并持续思考知识如何改变感官经验。另一件作品《Fitzcarraldo对音乐的爱,在哪都限制不了》,其灵感显然来源于1982年沃纳·赫尔佐格(Werner Herzog)的《陆上行舟》(Fitzcarraldo)。电影寓言了南美洲现代启蒙的理想与悲壮失败,而翟倞的绘画则让醉酒的舞动身影包裹在西装、领带、墨镜之下,精准捕捉了当代都市人内里的非理性与节奏感。这与他对音乐和电影的长期兴趣有关——旋律、节奏和片段式的影像经验,已然内化为绘画叙事的潜在结构。

▲翟倞,Fitzcarraldo对音乐的爱,在哪都限制不了,布面油画,231 × 180 cm,2025 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, Nothing can hold back Fitzcarraldo's love for music, Oil on canvas, 231 × 180 cm, 2025 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

对于观者而言,这种在不同作品情景间跳跃的观展体验,正如艺术家所阐述的,是在 “构建一个意义链条,用以对抗艺术话语中的‘祛魅’。”作品与作品之间松散的链接,促成了意义的叠加与衍生,从而不断生成新的解读。艺术家进一步提出了一个更具挑战性的概念:“相较‘祛魅’,或许‘赋魅’才是艺术实践中更棘手,且更难实现的目标。”他解释道,艺术可能需要这样一种主动的“赋魅”过程,为事物重新附着上复杂、多层次的意义,以匹配我们已然无比复杂的现实生活。他期望自己的绘画能“有感而发”,其意义生成“并非简单地从实到实,而是在虚与实之间轮回、转换的状态。”

在《你的忧伤,也是我的忧伤》中,金花的形象被置入与朋友、宠物、醉酒场景并列的环境里,从而脱离了单一的民族语境,成为一种可供普遍共情的姿态和目光。艺术家的“忧伤”源于其北京工作室遭遇拆迁的个人经历,这与彼时他观看电影《五朵金花》的感受偶然叠加,衍生出一种既关乎特定文化的记忆,又能被观者广泛投射的情感。金花由此从一个固定的民间传说符号中解放出来,与艺术家的私人经验紧密交织,极大地拓展了叙事的开放性。

▲翟倞,你的忧伤,也是我的忧伤,布面油画,65 × 50 cm,2024 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, Your blue is also my blue, Oil on canvas, 65 × 50 cm, 2024 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

另一个有趣的现象是,翟倞笔下的动物往往被赋予某种拟人化的灵性。在《一个崭新的,美好的生活就要开始了!》中,主角是名为“阿铁”的狗。它因受伤而被收养的现实经历,使其在画布上天然成为连接人类与非人情感的媒介。它的存在不仅为画面增添了情感的重量,更让日常经验获得了图像化的延展。然而,如何描绘这只朝夕相处的宠物,尤其是它那“可怜兮兮”的眼神,曾让艺术家感到困惑。转机来自他钟爱的一部小说——安东·契科夫的《带小狗的女人》。翟倞从故事中领悟到关键:“我认为狗作为小说的标题,恰恰暗示了它的‘不重要’——它在主要情节中从未出现。就像契诃夫用雅尔塔的风光与建筑等‘闲笔’来映衬男女主人公内心的焦灼一样,环境本身成了情感的镜子。那一刻我知道该如何画阿铁了。他不是一个需要被同情的主角,而是一个‘旁观者’。” 于是,在画作中,艺术家赋予了阿铁巨大的体量,并通过其与周遭作品若即若离的布展关系,进一步强化了这种“旁观”的疏离感。无论是《一个用雪花写字的诗人》中从高处伸出的手指,还是《一种倾向于沉思的生活》里苦思冥想的人物,其神态都与阿铁有着微妙的相似。通过作品间的并置与互文,阿铁的角色便从文学中的“闲笔”,转化为一个见证所有日常发生的、沉默的观察者。它背对画面深处的事件,却转头回望,仿佛在邀请观者一同审视这熟悉而又陌生的一切。

▲翟倞,一个崭新的,美好的生活就要开始了!,布面油画,180 × 135 cm,2025 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, A brand new and good life is just around the corner!. Oil on canvas, 180 × 135 cm, 2025 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

《勃鲁盖尔的神秘世界》中的绿色兔子,则是对尼德兰绘画传统的直接回应。勃鲁盖尔擅长在宏大的场景中嵌入精妙的细节,从而将日常景象点化为深刻的寓言。翟倞不仅通过一只被陌生化处理的绿色兔子致敬了这一传统——使其既是奇特的物种,也承载着内在的叙事逻辑——同时,他也将北京工作室后那片熟悉的小树林绘入其中。这使得作品的意涵超越了画面构成的“合理性”,它既勾连着艺术家个人的一段记忆,也邀请观者在现实与寓言、此地与异域之间自由游走。

▲翟倞,老彼得·勃鲁盖尔的神秘世界,布面油画,80 × 105 cm,2025 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, The mysterious world of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Oil on canvas, 80 × 105 cm, 2025 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

对异质性的探索同样体现在物象的非常规安排上。《时间的外面》中,一盏灯遮盖乃至取代了人物的头部。它不再仅仅是物理的光源,更在叙事层面制造了一种悬置感,打破了画面的稳定结构,迫使观众重新思考物象在叙事中的能动性。而在肖像作品《何为好的生活》中,艺术家以私人照片为基础完成的自画像。用旋涡式的结构、粗粝的线条与强烈的色彩,在表现主义风格与深刻的自我追问之间取得了平衡。作品的核心议题并非自我再现,而是将“何为好的生活”这一哲学命题,付诸一场视觉化的思考。

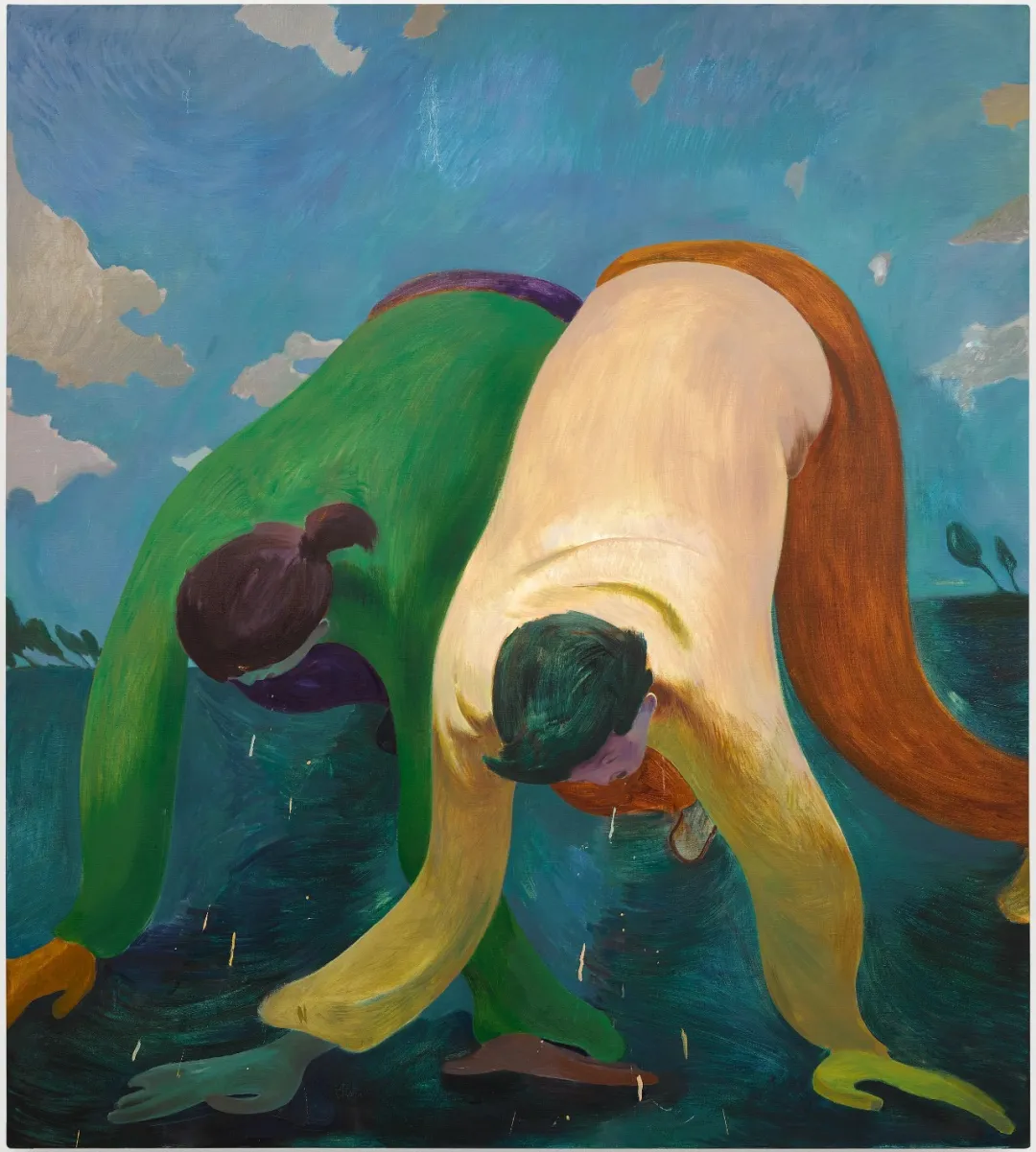

▲翟倞,时间的外面,105 × 80 cm,布面油画,2025 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, The outer layer of time, 105 × 80 cm, Oil on canvas, 2025 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

“日常生活的颂歌”集中呈现于千高原艺术空间的一楼和三楼,观众在此空间的漫步,如同阅读一部长篇小说,从细节到整体,从物象的触发到氛围的弥漫,叙事层层铺展。所有元素共同构成一系列开放的故事,邀请穿行其间的观者用自己的经验去补全与投射。这场展览,全面展示了翟倞对日常生活的创造性重构。在他的画布上,凝视、记忆、虚构与象征相互交织,使得最普通的经验也获得了崭新的层次。托多罗夫曾用“歌颂眼前所见的事物”来概括十七世纪荷兰风俗画大师的精神核心。然而,在古典传统中,“颂歌”通常用于赞颂英雄与宏大事件;而在翟倞这里,“颂歌”首先是一种观看的立场与方法。那些看似琐碎的动作与瞬间,经由他的绘画,得以揭示出自身内蕴的复杂性与潜在能量。他让平凡的生活片段在画布上获得了被郑重“聆听”的可能,既承继了艺术史对日常的深情凝视,又凭借其私密的叙事与跨学科的知识视野,成功地将一己之日常,转化为一套具有普遍意义的、丰饶的视觉系统。

文:贺潇

▲翟倞,何为好的生活?,布面油画,100 × 80 cm,2025 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Zhai Liang, What is a good life?, Oil on canvas, 100 × 80 cm, 2025 © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

Zhai Liang Solo Exhibition:

In Praise of the Everyday

In Éloge du quotidien (Ode to the Everyday) by French writer Tzvetan Todorov, the “everyday” is endowed with a meaning that transcends the trivial. He emphasizes that authentic experiences of existence are not conveyed in grand historical narratives, intense political struggles, or lofty ideals; instead, they are often revealed in the seemingly insignificant fragments of daily life. This perspective urges us to re-examine the everyday, not as mere repetitions of the mundane, but as a latent force that forms the foundation of human existence.

For this reason, compared with epic imageries, the “everyday” has long swung between the peripheral and the center of art history. Dutch Golden Age genre and still-life paintings solemnized ordinary life through focused scrutiny of daily life; modernist painting often transformed everyday experiences into material for formal exploration. In the contemporary context, the quotidian has become as much a mode of representation as a way of generating thought. It is within this framework that Zhai Liang’s exhibition In Praise of the Everyday unfolds: through his recent painting practice, the artist interweaves personal experience, fictional narratives, allegorical imageries, and art-historical motifs, searching for meanings through the layers of everyday life, worthy of being “praised.”

▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

Entering the ground floor of A Thousand Plateaus Art Space, How wonderful it would be to be intoxicated on knowledge, A Charming Person, and an alarmed cat elevated on a staircase-like structure designed by Xiqi Design collectively convey a clear message: Zhai Liang’s paintings do not aim to construct complete narrative of events but instead focus on capturing fleeting instants and excavating their latent narrative intensity.

▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

Zhai Liang’s work extends on the openness and complexity found throughout art history. He absorbs formal strategies from Pablo Picasso and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, as well as Martin Kippenberger’s tactics of parody, using them to locate his positions between the modern and the contemporary. At the same time, he reads extensively (from Susan Sontag to media theory), and watches films voraciously, transforming theoretical insights and cinematic scenes into narrative units and internal rhythms of his paintings. This interdisciplinary mechanism of narration has shaped the evolution of his practice: the overtly political expressions in his earlier works gradually gave way to micro-narratives of everyday life. Yet the grand themes have not vanished; instead, like salt dissolved in water, they appear discreetly through specific details and individual experiences. Private scenes and broader social logics overlap on Zhai Liang’s canvas, allowing the works to transcend simple declarations of stance and assume complex structures open to multiple interpretations.

In recent years, Zhai Liang has paid increasing attention to fleeting gestures and glances of the figures in his works. He follows the movement of the gaze, capturing where the eyes fall, the midway state of an action, and the moment before completion, and uses these as keys to constructing narrative. His compositions do not rely on piling up props or symbols to enrich the story; instead, they use immediate, frontal framing to draw the viewer close enough to observe how a limb or arm reaches toward the edge of the canvas, as if the scene extends into the space we inhabit. Unlike the compositional order of classical painting that kept the viewer at arm's length, this approach pulls the viewer into the pictorial space. Dutch genre painters such as Jan Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch employed similar narrative strategies—whether portraying a woman pouring milk, children playing, or a soldier drinking, they captured everyday instants to evoke intimacy. On the contrary, Zhai Liang's distinctiveness lies in his emphasis on the expressive strength of gestures and gazes; his aim extends beyond mere representation. In continuing the immediacy of the Dutch tradition, he further foregrounds "observing” as an experiential process.

▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

The experiential quality Zhai Liang presents often emerges from the interplay of memory and fiction. A Friend From Afar Comes to Visit draws on a real episode the artist experienced on the beach in Beidaihe: while inebriated, he and a friend encountered swarms of small crabs at night. Depicted as portraiture, they become estranged beings, akin to visitors from another planet. The title borrows a classic phrase from The Analects, but shifts the “visitor from afar” from human to small creatures of nature, transforming a personal memory into an allegorical narrative. A similar transformation occurs in Drink the Sea Dry, which combines the gesture of drunkenness, the imagery of seawater, and the act of pouring. The wine bottle echoes the sacred vase of Guanyin: one symbolizes worldly consumption and loss of control, the other religious bestowal and compassion. Their overlap grants everyday objects symbolic meaning, allowing religious imagery to settle into the mundane.

The motif of “intoxication” runs like a faint thread throughout the exhibition—vomiting, dancing wildly, bodies collapsing—lays down a foundational narrative ground. If Only There Were a Kind of Intoxication Born of Knowledge depicts a drunken instant. Yet, its title implies another possibility: if intoxication were produced by the fullness of knowledge rather than alcohol, how would life be reshaped? This hypothetical desire is rooted in Zhai Liang's extensive reading across philosophy, literature, and media theory, as well as in his sustained reflections on how knowledge alters sensory experience. Another work, Nothing can hold back Fitzcarraldo’s love for music, clearly draws inspiration from Werner Herzog’s 1982 film of the same title, a tale of the idealism and tragic failure of the modern Enlightenment in South America. In Zhai Liang’s rendition, the drunken dancing figure, wrapped in a suit, tie, and sunglasses, precisely embodies the irrational pulsations and rhythmic impulses of contemporary urban life. This relates to his long-standing interest in music and film—melody, rhythm, and fragmentary cinematic experience have already become latent structures in his pictorial narratives.

▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

For the viewer, the experience of moving through different works feels—just as the artist himself describes—like “constructing a chain of meaning to resist the ‘disenchantment’ of artistic discourse.” The loose links between works generate layers of meaning and proliferation, continually producing new interpretations. The artist proposes an even more challenging concept: “Compared to ‘disenchantment,’ perhaps ‘re-enchantment’ is more challenging and a more necessary aim of artistic practice." He explains that art may require an active process of re-enchantment—of restoring complex, multi-layered meanings to things to match our overwhelmingly complex contemporary reality. He hopes his paintings are "emotionally driven," and that meaning is generated "not simply from reality to reality, but in a cyclical, shifting state between the virtual and the real."

▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

In Your Sorrow Is Also My Sorrow, the figure of Jin Hua is placed alongside friends, pets, and drunken scenes, thus escaping a singular ethnic context to become a posture and gaze capable of universal empathy. The artist's "sorrow" stems from the demolition of his Beijing studio—a personal event that coincided with his viewing of the film Five Golden Flowers, generating a layered emotion that is at once tied to a specific cultural memory and widely relatable to viewers. Jin Hua thus becomes liberated from a fixed folkloric symbol and interwoven with the artist’s private experience, greatly expanding the narrative’s openness.

Another noteworthy aspect of Zhai Liang’s paintings is the anthropomorphic spirituality he often grants to animals. In A Brand-New, Beautiful Life Is About to Begin!, the protagonist is Atie, a dog the artist adopted after it was injured. Its real-life experience naturally positions it as a mediator between human and non-human feelings. Its presence not only adds emotional weight but extends everyday experience into imagery. Yet the question of how to paint this dog he lived with—whose “pitiful” gaze mesmerizes—once troubled the artist. The turning point came from one of Zhai Liang’s favorite novels, Anton Chekhov’s The Lady with the Dog. Zhai realizes from the novel that, “I think the dog being in the title hints at its ‘sidelined’ role—it never appears in the main narrative. Just as Chekhov used the scenery and architecture of Yalta as ‘idle brushstrokes’ to reflect the inner turbulence of the protagonists, making the environment a mirror of their emotions, that was when I knew how to paint Atie. He is not a protagonist to be pitied; he is a ‘bystander.’” Thus, in the painting, the artist gives Atie an exaggerated scale, and through its subtly distant relationship with surrounding works, strengthens its sense of detachment. Whether the hand reaching down from above in The Poet Who Writes with Snowflakes, or the contemplative figure in A Life Inclined Toward Reflection, their expressions bear a quiet resemblance to Atie’s. Through juxtaposition and intertextuality, the dog’s role shifts from a literary "idle brushstroke" to a silent witness to daily events. Though turned away from the deeper events of the scene, he looks back as if inviting viewers to examine this familiar yet bewildering world alongside him.

▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

The green rabbit in The Mysterious World of Pieter Bruegel the Elder is a witty response to the Netherlandish painting tradition. Bruegel excelled at embedding intricate details within vast scenes, turning the quotidian into profound allegories. Zhai Liang not only pays homage through the estranged depiction of a green rabbit—at once an unusual species and a bearer of inner narrative logic—but also paints a small grove in the background behind his Beijing studio. This extends the work beyond compositional “plausibility,” linking it to the artist’s personal memory and inviting viewers to move freely between reality and fable, between the familiar and the foreign.

▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

This exploration of heterogeneity also appears in the unconventional arrangement of objects. In The outer layer of time, a lamp covers—and even replaces—the figure’s head. It becomes more than a physical light source, creating a sense of narrative suspension, destabilizing the picture, and forcing viewers to reconsider the agency of objects in storytelling. In the portrait What Is a Good Life, the artist paints a self-portrait from a personal photograph. With swirling structures, rough lines, and intense colors, the work on canvas balances expressionist aesthetics with deep existential inquiry. The core issue is not self-representation, but a visualized reflection on the philosophical question: “What is a good life?”

▲展览现场 ©艺术家及千高原艺术空间

Exhibition View © Courtesy of the Artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space

In Praise of the Everyday unfolds across the first and third floors of A Thousand Plateaus Art Space. Walking through the exhibition resembles the experience of reading a novel, where narrative spreads from details to the plot, from material triggers to atmospheric diffusion. Every element forms an open constellation of stories, inviting viewers to complete and project meaning through their own experiences. This exhibition stages Zhai Liang’s creative reconstruction of everyday life. On his canvases, observation, memory, fiction, and symbolism intertwine, conjuring layers of meaning to the most ordinary experiences. Todorov once summarized the spirit of 17th-century Dutch genre painters as “singing the praises of the things right before our eyes.” Yet in classical tradition, the “praise” was typically reserved for heroes and monumental events. For Zhai Liang, however, the “ode” is first a stance and a method of looking. Gestures and instants that seem trivial are revealed through his painting to possess inner complexity and latent potential. He allows ordinary fragments of life to be “heard” with attentiveness on the canvas—continuing the art-historical devotion to the everyday while, through his intimate narratives and interdisciplinary intellectual vision, elevating everyday experience into a visual system of universal resonance.

Text / Fiona He

关于艺术家

从“小径分叉的花园”到“夜航船”系列中的“目录—通天塔图书馆”和“笔记”,“寻隐者”,以及接下来的“日常生活的颂歌”,翟倞善于凭借其画作中若隐若现的象征,将观者引向某些文学时刻——小说和电影中的诙谐片段、生活里亦真亦幻的顿悟和想象、耐人寻味的社会关系……把阅读的文本和个人当下或过去的记忆,如同回声共振一般,融合在一幅幅画作之中。

艺术写作者,独立策展人,资深艺术类翻译。她曾任职于亚洲艺术文献库中国大陆研究员和艺术论坛中文网编辑。

她长期关注传统创作媒介在科技环境中的演变,与艺术展示的政治。

©文章版权归属原创作者,如有侵权请后台联系