只要有了钥匙,就可以再回去

这篇文字无意对艺术家进行心理侧写或挖掘隐秘,更像是一种友人之间的闲聊,他的绘画想通过那非诗歌,非语言的方式做一次只属于自己的深呼吸。如果这篇文章被他选择发出,那代表他在这样的休憩之后,愿意向大家诉出他对于世界的亲昵。

颜真卿楷书字体:贺勋

Yan Zhenqing Regular Script Font: He Xun

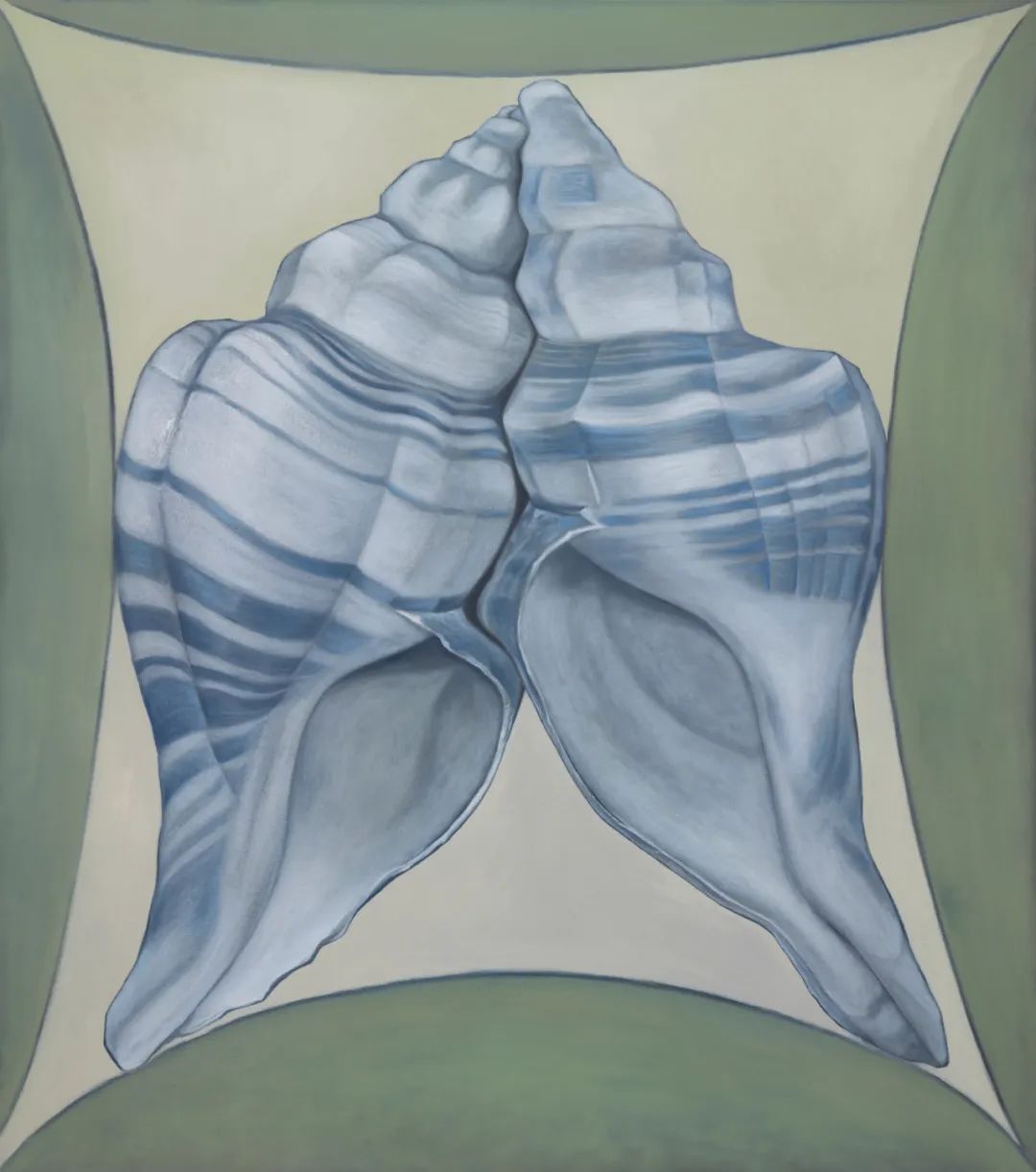

贺勋所画的物件大多以成双成对的方式出现,他说的自己的名字“贺勋”也是双生结构,这是一种命运使然。我好奇地将贺/勋二字拆开,变成“加”,“口”,“贝”。而我把重点放在了重组后的二字:叻与贝。叻是在宗教仪式中的常见咒语,而贝即是贝类,贺勋二字成为了两枚相同法螺的指代,业力一般的文字游戏更加扑面而来,这时不仅双生结构成为了一种注定,海螺形象的出现也成为了因果的必然。

静物-凡人之家|Still Life – House of Mortals

木板油画 | Oil on panel 50×60cm

2025

我看着海螺和朋友开玩笑说,他想画的不是海螺,而是裸体(螺体)。我的谐音烂梗总被朋友批评,所以偶尔我会拿出几句精神分析理论据理力争,给自己的低级创造强词夺理一番。在《诙谐及其与无意识的关系》中弗洛伊德指出,被压抑的欲望可以通过伪装的形式得到释放,而类似双关语的幽默就承担着这种释放功能。当然来访者有时并非有意设计双关,而是在无意识中选择了能承载多重含义的语言形式,对我来说,抛开与宗教的联系,海螺可能也是这样的伪装形式。

弗洛伊德:诙谐及其与无意识的关系

Sigmund Freud: Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewussten

1905

入口左边由海螺组成的凡人之家被耀眼的“圣光”照亮,走进通道深处,我的瞳孔不可避免地缩成一团阻挡光线的冲击。在调整后的低ISO状态下,正常的展厅灯光变得像吃完咸菜再吃青菜一样寡淡,再回头看火光四射的画面,如同回到远古时期的寒冷冬夜,人们在篝火旁赤身螺体维持体温,使得让文明得以存活。

飞鸟寺|Temple of the Flying Birds

布面油画 | Oil on canvas 200×600cm(双联)

2025

在记忆之河中躺着发呆是人们殊途同归的习惯。画廊第二个空间中,飞鸟寺的记忆与种子同时出现。种子在藏传佛教中种子Bīja (बीज)指潜在的心识能量,又或是一种业力储存,就像被埋藏的记忆影响着未来。飞鸟寺(2025)中的符号如其名字一样滑翔在记忆之寺中,这被时间与潜意识的防御机制刻意扭曲的记忆,成为他清醒时的梦。通向外界窗户被放置在两幅拼接画之间,那是“空隙中的空隙”,但在画面中并没有看到任何符号有飞离这荒诞空间的迹象。贺勋允许符号碎片在记忆的笼中反复弹跳飞翔,这比让它们逃离来的更有意义,好似小时候Windows XP上的三维弹球游戏,为了获得更多积分,我们总是不让小球逃走,任凭它在各个机关中来回碰撞。

Cinematronics:三维弹球 太空军校生 | Full Tilt! Pinball Space Cadet

电子游戏 | Video Game

1995

在贺勋的生活中,“哥”早已成为他的口头禅,他对朋友如家人般热烈,甚至不熟悉他的人会感受到扎人似的亲密,如同海螺上尖锐的刺。在后续的几张与海螺相关的大画中,海螺们通过各种体态变化将自己的空缺填补,或者如拼图一样双生结构组成更完整的身体。这些海螺变成了一种艺术家自画像式的存在。双生海螺如被重组的两组“叻贝”,不停的书写自己的名字。他把记忆寄存在飞鸟寺中,海螺的空洞是聆听回声的钥匙,这钥匙仍然攥在他的手里。飞鸟,灯盏,海螺,双生…他站在画面中向大家坦诚相见,坚强的通过旋转、重叠,进行着自我修补。那是艺术家仰卧在记忆之河中回归亲密的渴望,还有他所自顾自的担负着的,让大家温暖起来的长兄般的责任。

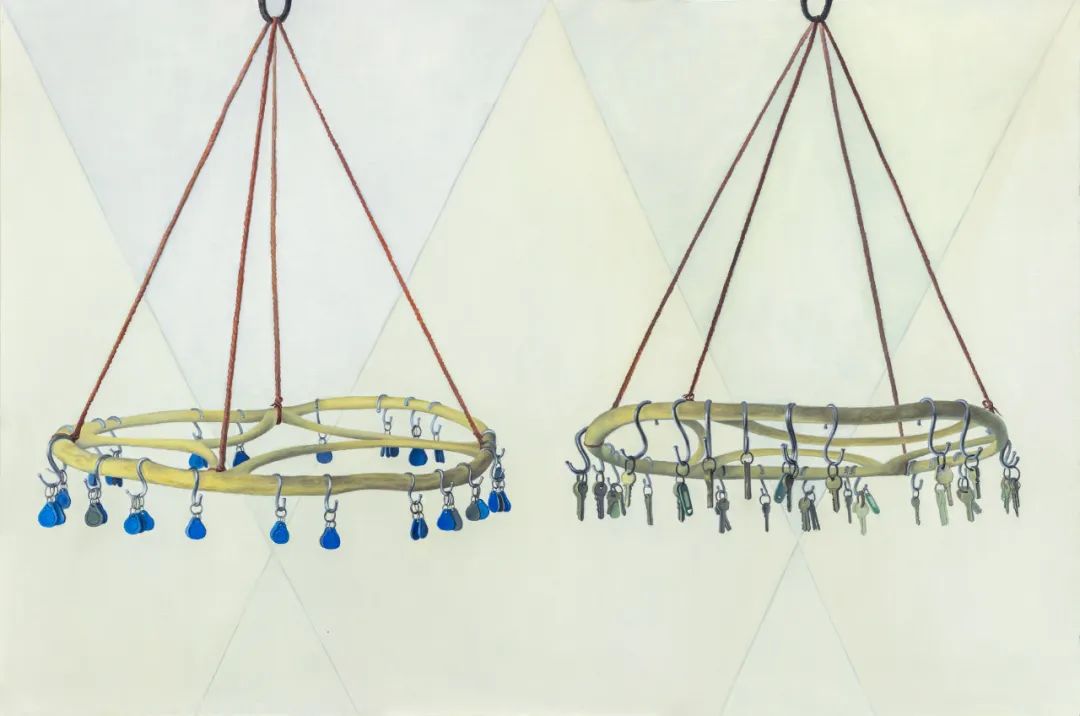

你的左我的右| Your Left, My Right

布面油画 | Oil on canvas 170×150cm

2024

这篇文章四处充斥着各种谐音烂梗,临离开展览前我说,我又想到一个,应该把展览的英文名“Keys”改叫“Kiss”,这样你可以更放肆地表达出对本应的暧昧与亲昵,他说:“这个梗不错,要不你写个展评得了。”于是有了这些字。而我也默契的把展评的诞生契机留在了文章最后,和那两把在展览末尾的钥匙一样。这种头尾相连的回归架势延续着贺勋一如既往的创作结构,正如在早期作品:永恒的爱到来又离开(2015)中,象征着磁力的虚线以弧形从磁铁上发出又归返。

钥匙 |Keys

布面油画 | Oil on canvas 130×195cm

2024

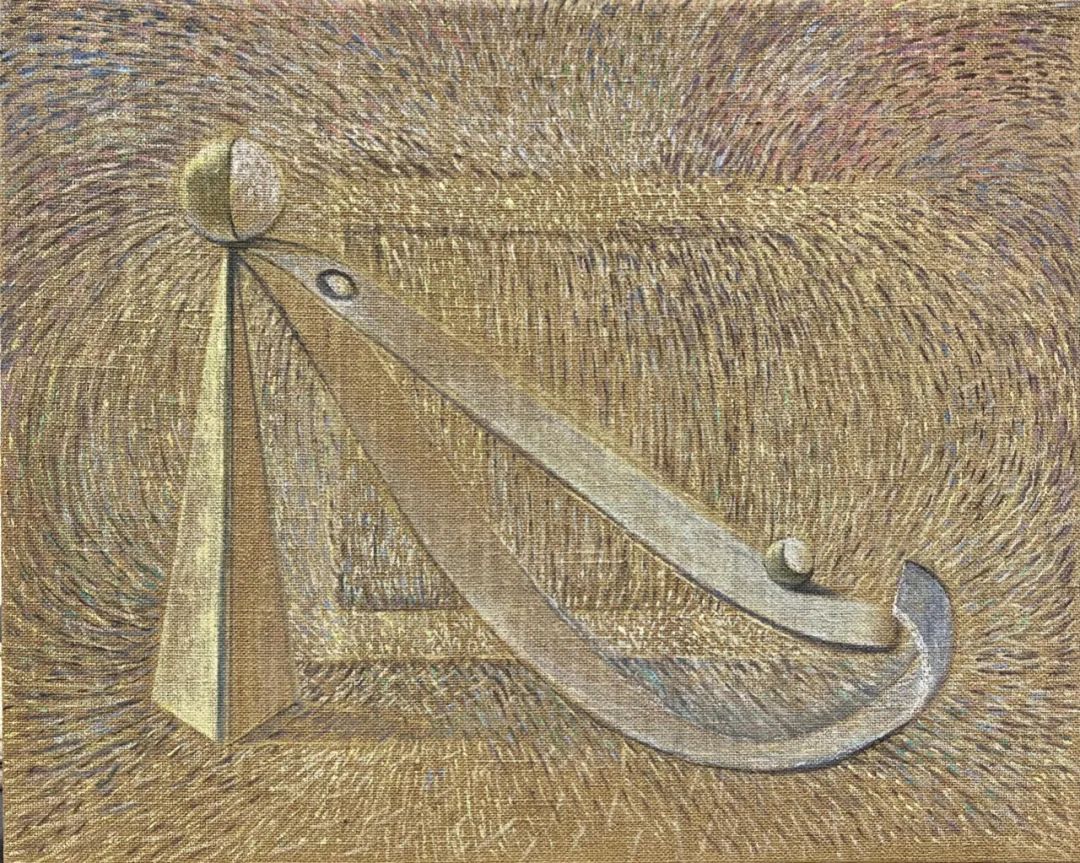

永恒的爱到来又离开|Eternal Love Comes and Goes

布面油画 | Oil on Canvas 80×100cm

2015

大日如来经中所探讨的“阿字本不生”,何尝不是这个展览的一种投射,双生结构的钥匙作为互为缘起的幻想,空洞的海螺代表了容纳记忆回声的“空”,而钥匙作为开显与闭合的辩证,成为了封印又是解印。

只要有了钥匙,就可以再回去,而海螺里总能听到回响。

记于2025年5月25日

耿大有

Geng Dayou on He Xun: "With the Key, One Can Always Return"

This text does not seek to psychoanalyze the artist or excavate hidden truths. It is more akin to a casual conversation between friends. His paintings attempt, through non-poetic and non-linguistic means, to take a deep breath that belongs solely to himself. If he chooses to publish these words, it signals that after such respite, he is ready to share his tender intimacy with the world.

In He Xun’s paintings, objects often appear in pairs—a duality mirrored in the twin structure of his own name, “贺勋” (He Xun), as if ordained by fate. Playfully dissecting the characters, I split “贺” into “加” (add) and “口” (mouth), and “勋” into “贝” (shell). What emerges are two reborn fragments: “叻” (a syllable often chanted in rituals) and “贝” (shell). The name “He Xun” thus transforms into twin conch shells, their karmic wordplay resonating like a mantra. Here, duality is not merely fated; the emergence of the conch becomes an inevitability of cause and effect.

Staring at the conch, I joked to a friend: perhaps what he paints is not the shell (螺体) but the nude (裸体). My affinity for clumsy puns often draws scoffs, so I occasionally arm myself with psychoanalytic theory to defend my linguistic mischief. In Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Freud posits that repressed desires find release through disguised forms, with puns acting as vehicles for such liberation. Visitors to his works may not consciously design these double entendres, yet unconsciously, they gravitate toward language—or imagery—that harbors layered meanings. For me, stripped of its religious connotations, the conch becomes such a vessel of disguise.

To the left of the entrance, a mortal dwelling woven from conch shells is bathed in blinding “holy light.” As I venture deeper into the passage, my pupils contract defensively against the glare. Under the adjusted low ISO setting, the gallery’s ordinary lighting turns as insipid as chewing greens after pickles. Turning back to the radiant canvases feels like returning to an ancient winter night, where ancestors huddled naked by fires, their bodies and shells intertwined to sustain the fragile flame of civilization.

Lying adrift in the river of memory is a habit shared by all. In the gallery’s second space, the recollections ofTemple of the Flying Birds (飞鸟寺) coalesce with seeds. In Tibetan Buddhism, the seed—bīja (बीज)—symbolizes latent mental energy, a karmic reservoir. Like buried memories shaping the future, the glyphs in Temple of the Flying Birds (2025) glide through this temple of remembrance, their forms warped by time and the subconscious’s defense mechanisms, becoming dreams he revisits in waking hours. A window to the outside world is inserted between two spliced paintings—a “void within a void”—yet no symbol shows any intention to escape this absurd realm. He Xun permits fragmented signs to ricochet endlessly within memory’s cage, a choice more meaningful than liberation. It recalls the old Windows XP pinball game: to score higher, we never let the ball escape, delighting in its collisions.

In He Xun’s life, the word “bro” (哥) has long become a mantra. He greets friends with familial fervor, his warmth so intense it sometimes prunes like the sharp spines of a conch. In subsequent large-scale conch paintings, the shells contort to fill their own voids or merge like puzzle pieces into fuller bodies through dual structures. These conchs morph into artist self-portraits. Twin shells, like the rearranged “叻” and “贝,” ceaselessly inscribe their own names. He deposits memories in Temple of the Flying Birds; the conch’s hollow becomes a key to echo-chambered recollections—a key still clutched in his palm. Birds, lamps, conchs, duality… Standing bare within the frame, he mends himself through rotation and overlap: an artist reclining in the river of memory, yearning for intimacy while shouldering an elder brother’s duty to keep others warm.

This text brims with dreadful puns. Before leaving the exhibition, I quipped, “Another idea: rename the show ‘Keys’ as ‘Kiss’—to better indulge in the ambiguity and intimacy it deserves.” He laughed, “Not bad. Why don’t you write the review yourself?” Hence these words. I’ve tactfully embedded the review’s origin here at the end, mirroring the two keys displayed at the exhibition’s close. This cyclical return echoes He Xun’s enduring creative structure, reminiscent of his early work Eternal Love Comes and Goes (2015), where magnetic dashed lines arc away only to reunite.

Is the Mahavairocana Sutra’s concept of “the primal unborn syllable “A”(saṃskṛtam : aka^ra-a^dyanutpa^dah) not a reflection of this exhibition? The twin keys, fantasies of interdependent origination; the hollow conch, an emptiness cradling memory’s echo; the key itself, a dialectic of revelation and closure—both seal and solution. With the key, one can always return. And within the conch, the echo forever lingers.

Written by Geng Dayou

May 25, 2025

©文章版权归属原创作者,如有侵权请后台联系删除