| 香格纳上海西岸空间正在展出朱加个展《近期的绘画》,展览将持续至10月18日。 作为中国录像艺术最早的实践者之一,朱加和他的作品在中国录像艺术史上占据了重要的位置。此次展览同样得到了广泛关注,世界顶级艺术杂志ArtReview主编Mark Rappolt为其撰写了评论文章,并由复旦大学新闻学院副教授徐佳译成中文与大家分享。 |

We live in a time when the idea of sociability is a fraught one. We've learned new phrases like ‘social distancing’ and ‘lockdown’, and, for the majority of us, experienced, in some way, the reality of what they mean. We’ve learned that other people’s bodies are potential toxic threats. And we’re being trained to avoid them. It’s in this context that Zhu Jia’s latest series of paintings, recording social encounters in London and on his travels outside his native China, arrive.

Today, as we look at his renderings of sunbathers, loungers, picnickers and chatterers it almost seems as if they are records of another time. And indeed they are, having been, in the main, executed during the three years prior to the age of the virus. But time and circumstance have a habit of changing the way in which we read words, images and things. And much of Zhu Jia’s work, from early videos such as Forever (1994), has been about trying to keep up.

展览现场 Installation views

我们正生活在一个恐惧社交的时代。我们学习了诸如“社交隔离”、“封城”等新的词汇且我们当中的大部分人以这样或那样的方式经历了这些现实。我们被告知他人的身体可能是有毒的,我们被规训去远离他人。正是在这样的语境下,朱加新展《近期的绘画》开幕了,这一系列作品基于艺术家在伦敦生活的社交际遇记录。

今天我们观看他笔下那些晒着日光浴、野餐或闲聊的人们,仿佛是在观看另外一个时代的记录。的确,大部分画作是疫情爆发之前三年间创作的,或许真的是来自“另外一个时代”吧。然而时间和环境总是在改变着我们阅读文字与观看图像的方式,而从他的早期录像作品《永远》(1994)以来,朱加的许多作品都在试图跟进。

展览现场 Installation views

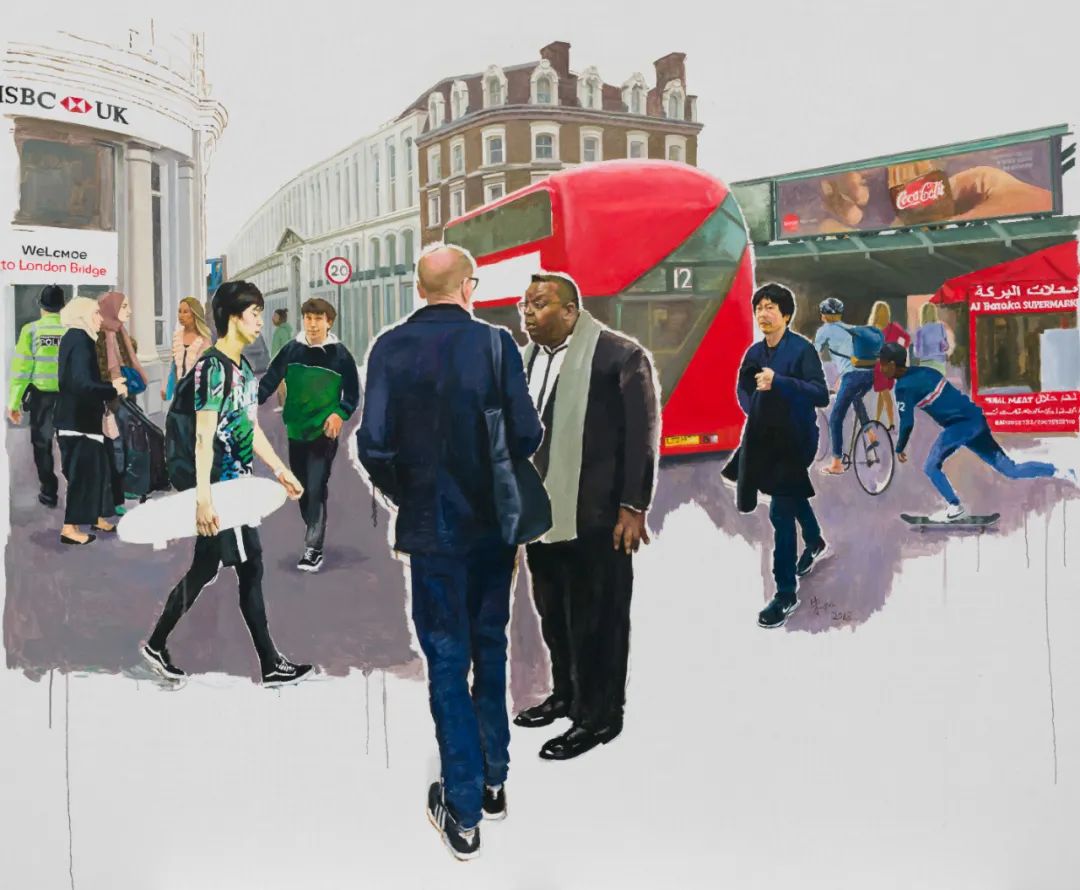

Perhaps that’s why the dripping paint in Hello London 2 (2018), suggesting a rapidity of execution, makes us feel as if the artist is trying to capture something that is already slipping away. A memory threatening to become as blank as the empty canvas that makes up the lower part of the painting, which depicts the artist strolling behind one of London’s red buses, presumably to meet fellow artists Christian Marclay and Isaac Julien, pictured in the foreground, already engaged in deep conversation, while a multi-ethnic crowd passes by. Zhu Jia offers us a sideways glance. He’s not yet a part of the conversation, and neither are we. Both the artist and the viewer stuck on the outside. Moreover, we’re left wondering whether or not the London Zhu Jia is rushing to greet is constituted by the place, or the people who live there: his friends. Indeed, in this work, the London made up of red buses, banks, food stores and Georgian architecture seems little more than a stage set for the principal figures, who, outlined in white, look as if they have been collaged in.

《伦敦你好-之二》(2018)中滴淌着的颜料揭示着某种转瞬即逝,令人觉得艺术家在试图抓住某些已经开始流失的东⻄。如画布下半部分的留白,对所描绘的这一瞬间的记忆仿佛白驹过隙——艺术家本人步行在一辆伦敦的红色公交⻋后方,可能是去和出现在画面前景、同为艺术家的Christian Marclay和Isaac Julien会面,二人已经在交谈,而朱加旁视的眼光告诉我们他并不是交谈的一部分,我们也不是,艺术家和观众皆置身局外。在背景中,一个多元种族人群路过。除此以外,我们好奇朱加赶来结识的伦敦究竟是一个地方还是一群人(一群他的朋友)。事实上,在他的作品中,那个由红色公交⻋、银行、⻝品商店和乔治式建筑构成的伦敦无非是为那些人物搭建的一个舞台,那些以白色轮廓线勾勒的人物仿佛是被拼贴进画面的。

朱加 Zhu Jia | 伦敦你好-之二 Hello London-2 | 布上油画 Oil on canvas | 200(H)*240(W)*5cm | 2018

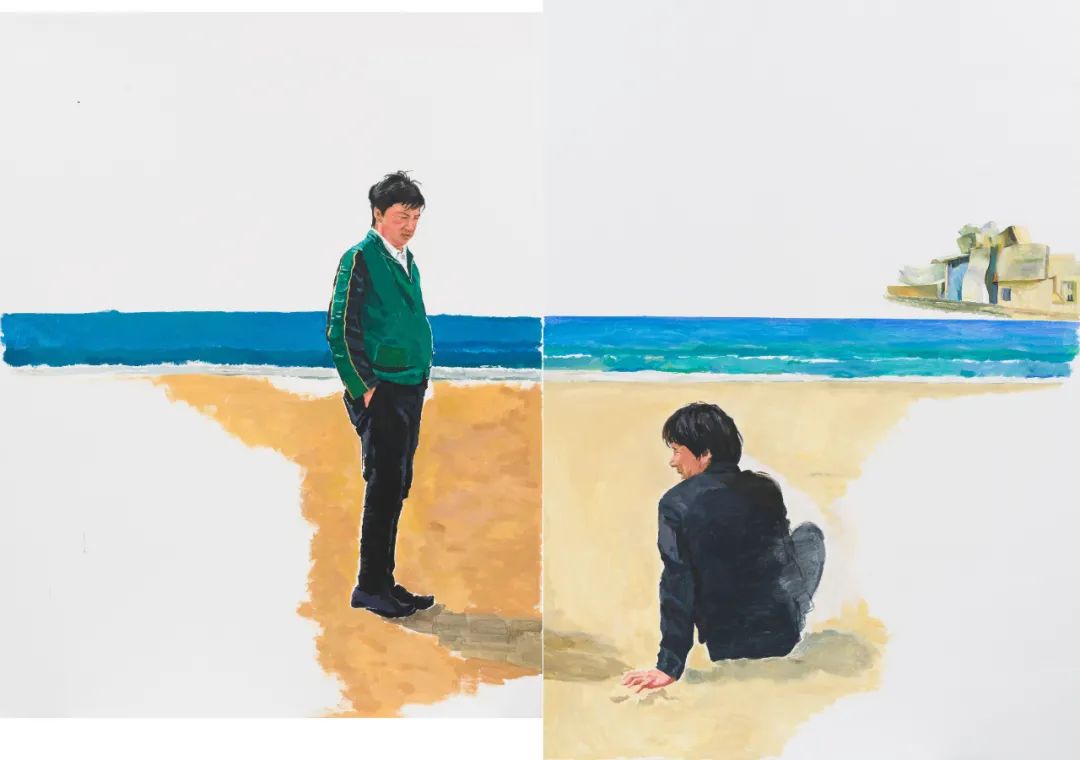

This sensation is further heightened in the diptych Scenery Near Bilbao (2018), in which the ‘scenery’ is a sketchy beach and strip of blue, with the flowing metal and concrete of Frank Gehry’s iconic Guggenheim Museum a footnote in the distance, sent to the top lefthand corner of the painting, almost out of sight. The real ‘scenery’ is the dominant figures of Zhu Jia, with his back to us, smiling, sitting on the sand, and fellow artist Zhou Teihai staring down at his longtime friend. At first glance it’s the only time the artist seems fully engaged with another figure in this series of works, and yet the fact that each of the subjects in the painting is represented on a separate canvas, and that the watery blues of the sea and muddy yellows of the sand don’t quite match up, suggest that the scene is constructed, perhaps even performed, and that each character, despite an apparently shared moment, remains resolutely in their own space.

这种观感在《毕尔巴鄂附近的风景》(2018)中更为显著。所谓“风景”不过是速写的海滩和一条蓝色的水域,弗兰克·盖里著名的古根汉姆博物馆流线型的金属与混凝土外观在画面的右上⻆近乎看不⻅的远处做着一点注脚。真正的“⻛景”是背对着我们、面带笑容坐在沙滩上的朱加本人以及另一位艺术家周铁海,铁海俯视着他的老朋友。乍一看这似乎是整个系列当中艺术家与另一个人物真正完全相关的唯一场景,然而事实上,两个人物分布在两张画布上,而两片海域也呈现出不同蓝色的海水和⻩色的沙滩,这表明画面中的景观是被建构的甚至表演出来的,两个人物尽管彼此分享着这一时刻,却都坚定地置身他们各自的空间。

朱加 Zhu Jia | 毕尔巴鄂附近的风景 Scenery near Bilbao | 布上丙烯 Acrylic on canvas

| 205(H)*295(W)cm (in 2 pcs) | 2018

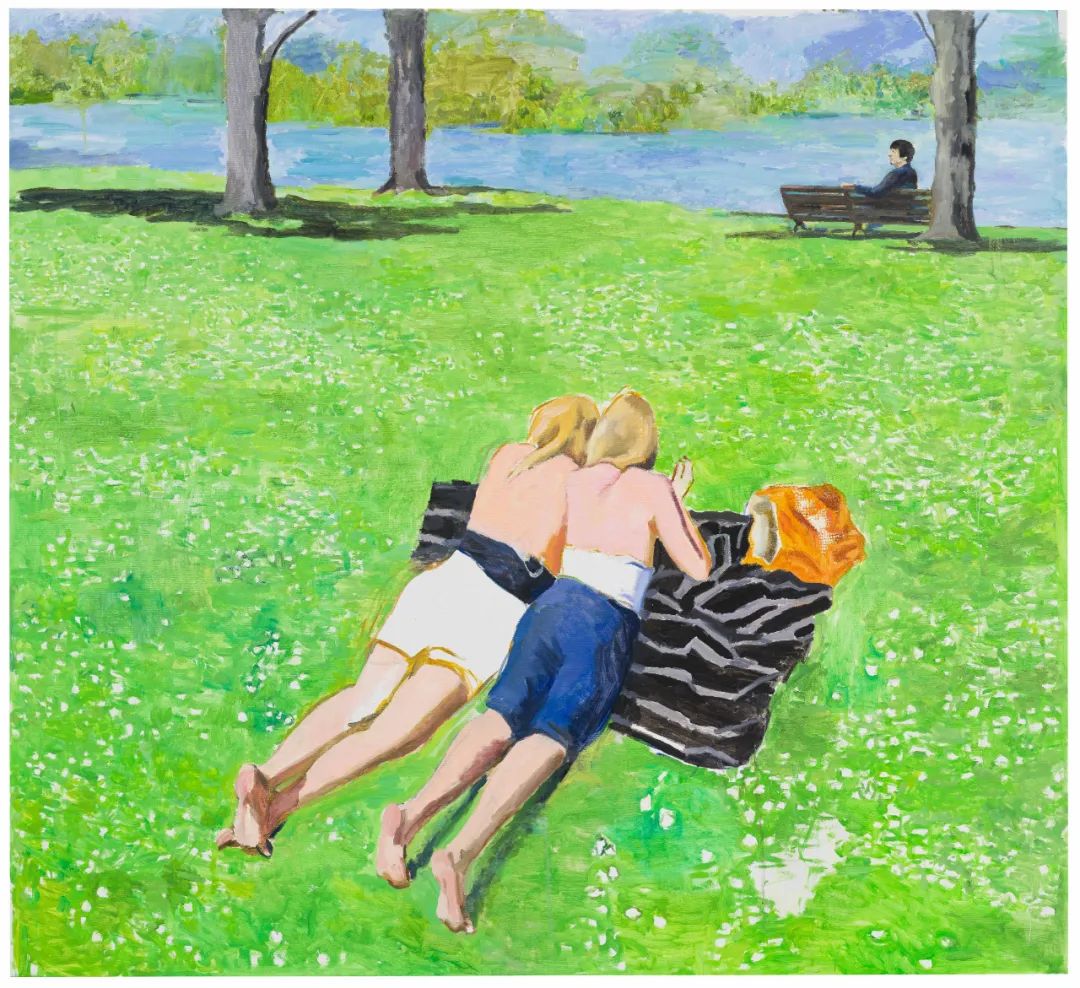

Collectively, Zhu Jia’s new works offer a spectrum of social encounters in which the artist is always present and always, to varying degrees, on the fringe. Not quite actually there. For all the fact that these works a realistically rendered as if they were episodes from the artist’s daily life. In The Spring and Sunbeam (2019) he’s on a bench, in the background, staring out into the distance and seemingly ignorant of the painting’s ostensible subject — a pair of female sunbathers whispering to each other on a blanket as they tan their backs — even if the evidence of the time he spent painting them tells us he was surely not. It’s in creating such subtle moments of confusion or uncertainty that Zhu Jia excels.

在朱加这一系列描绘社交场景的新作品当中,艺术家本人总是在场,且总是或远或近地位于画面边缘,或者说,他并不真正在场。这些作品仿佛是艺术家日常生活片段的写照。在《春日骄阳》(2019)中,他坐在背景中的一张⻓椅上, 眼光投向远方,似乎并不关注画作的主体——两名斜躺在草 地上晒着日光浴聊着天的女孩,然而他绘画她们所花费的那些时间揭穿了他。营造这样的混淆或不确定的微妙时刻正是朱加所擅⻓的。

朱加 Zhu Jia | 春日骄阳 The Spring and Sunbeam | 布上油画 Oil on canvas | 188(H)*205(W)cm | 2019

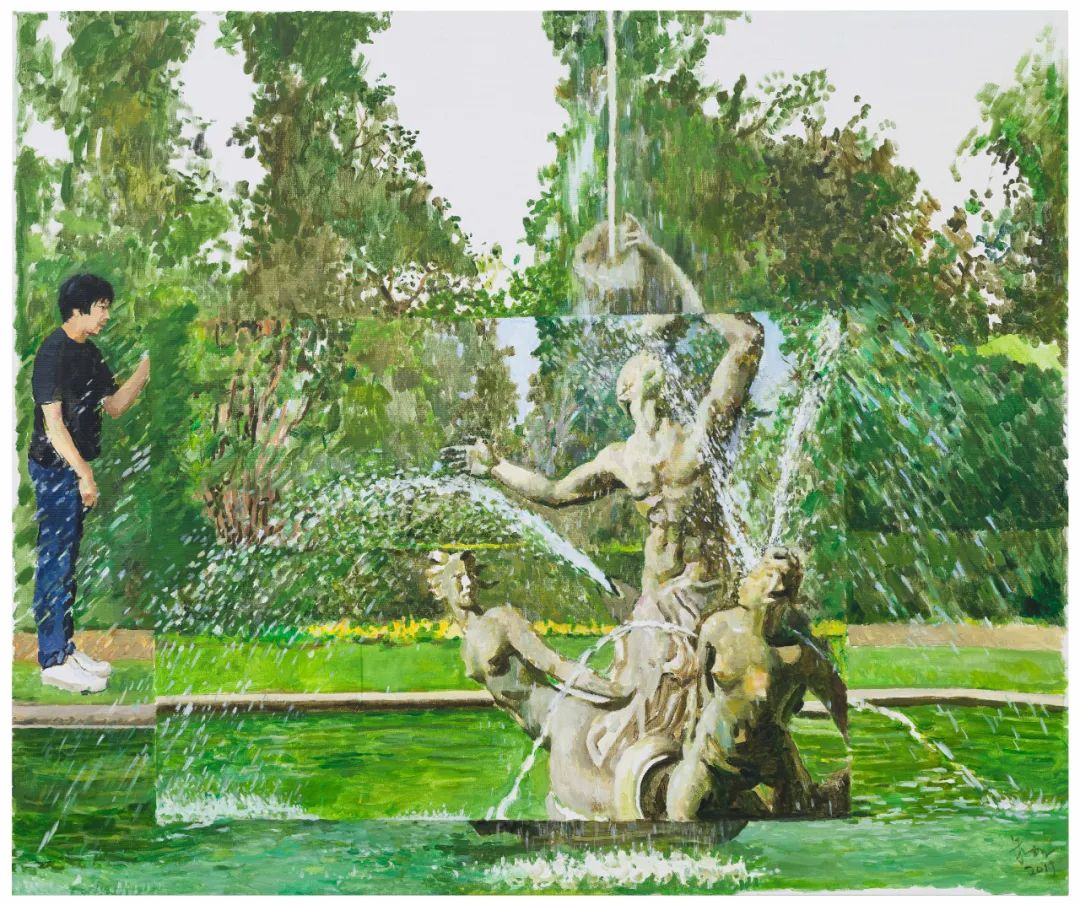

In Spray Fountain (2020) the artist is pictured taking a photograph of a classical fountain, shooting out jets of water inside a formal park. The central figures of the fountain’s statuary, however, are misaligned. Clearly collaged in from more than one perspective. We see a representation of the photograph of the fountain superimposed on the fountain. Although it’s unclear if that’s the photograph the artist is taking in the painting. (It’s perspectivally unlikely.) Indeed, it’s generally unclear where the ‘truth’ in this painting lies. The classical figures that make up the fountain start to look fake (a pretentious echo of a style that evolved in Greece and Rome rather than the London park in which the painting was set), the painting is of a photograph, and of the artist revealing his tricks (related to the videowork Zero (2012), in which the female protagonist wanders in and out of various stage sets and artificial scenes). And the whole thing is a stage set for an aggravated selfie, a demonstration of the artist’s presence (in more than one way) rather than of a portrait of a fountain at all. Our primary connection in all these works is with him.

朱加 Zhu Jia | 喷水池 Spray Fountain | 布上丙烯 Acrylic on canvas | 143(H)*170(W)cm | 2020

在《喷水池》(2020)中,艺术家正在拍摄公园里喷着水柱的池子,然而人物雕像却是偏移的、从不止一个⻆度拼贴过来的。我们看到的是一个置于喷水池之上的喷水池照片的表征(在透视法上这是不可能的)。事实上,我们找不到这幅作品中的“真相”。构成喷水池的古典人物开始显得有些假冒(它似乎是对希腊和罗⻢⻛格的刻意模仿,而并不属于画作所取景的伦敦公园)。作品是关于一张照片的,关于艺术家的一个戏法(与2012年的影像作品《零》相关,在其中女主⻆出入于各种舞台背景和人工场景中)。而整幅作品恰似一个增强版自拍的舞台,是艺术家(以不止一种方式)存在的宣告,根本不是对一座喷水池的描绘。在所有的作品中, 我们主要的关联都是与他之间的。

朱加 Zhu Jia | 零 Zero | 彩色喷墨打印 Colour inkjet print | 110(H)*139(W)cm | 2012

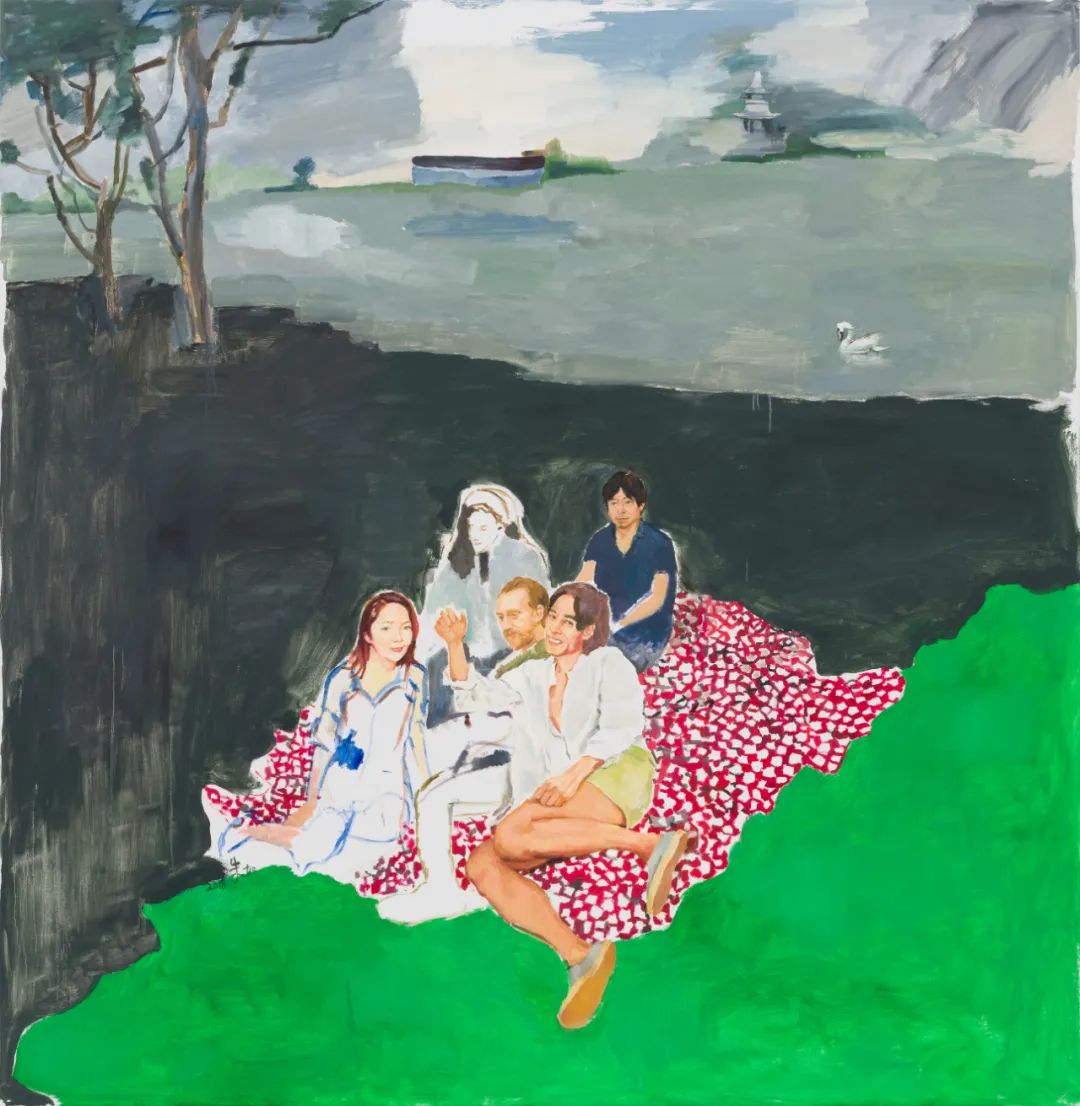

At the picnics in Summer Dinner (2018) and Summer Evening (2019) he stares out at us from the background or stands, arms folded, gazing into an empty patch of grass, while his friends (largely members of the artworld) laugh and chatter, engaged fully in paying attention to whatever it is their neighbours are saying. His poses are loosely reminiscent of the early photographic series My Space (1994), in which the artist’s younger self is pictured, dressed formally in a suit, looking by turns earnest and thoughtful while ‘trying out’ the beds, tables and chairs (presumably also imagining the characters and lifestyles they suggest) in a Beijing furniture store. The series is weirdly reminiscent of another, almost contemporary, depiction of the fantasies and alienation brought about by the onset of capitalism — Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho (1991): ‘there is an idea of a Patrick Bateman,’ the novel’s central character says of himself, ‘some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there.’ Though the scenery has changed and the characters too, there’s an ongoing sense in these new paintings that Zhu Jia is still trying to make himself present, so assert an ‘I’.

朱加 Zhu Jia | 夏日的晚餐 Summer Dinner | 布上油画 Oil on canvas | 200(H)*300(W)*5cm | 2018

朱加 Zhu Jia | 夏日的傍晚 Summer Evening | 布上丙烯 Acrylic on canvas | 155(H)*210(W)*5cm | 2019

在《夏日的晚餐》(2018)和《夏日的傍晚》(2019) 中,他或从背景中凝视着我们,或双臂交叉于胸前凝视着一块空的草地,而他的朋友们(大都是艺术圈成员)或欢笑或闲谈,完全沉浸在身边人们的言谈中。他的姿态有一些令人想起早期的影像系列《我的空间》(1994)——艺术家的年轻形象身着⻄装,在北京的一家家具店“试”床和桌椅,神情时而诚恳时而多思(可能在想象着这些家具所暗示的人物和 生活方式)。这一系列诡异地让人联想到布莱特·伊斯顿·埃利斯的小说《美国精神病人》(1991),小说描绘的是资本主义的幻像与异化——“存在一个关于帕特里克·⻉特曼的观 念”,小说的主人公自述道,“一个抽象的观念,但真实的我是不存在的,存在的只是一个物体,一个虚幻的物体;即便我可以掩饰我冷漠的眼神,即便你可以和我握手并感觉到我 的手掌紧握住你,你或许还可以感觉到你和我的生活方式是接近的,即便如此,我并不存在”。在朱加的这一系列新作中,虽然景观和人物都改变了,他依然在试图呈现他自己,在宣告“我”之存在。

朱加 Zhu Jia | 我的空间 My Space | 彩色喷墨打印,无酸相纸 Colour inkjet print, Acid Free Paper | 120(H)*120(W)cm | 1994

In a way, the artist’s position in all this fits the French writer Albert Camus’s description of Mersault, the central character in his celebrated 1942 novel The Outsider: ‘In a sense he is an outsider in the society in which he lives, on the outskirts of life, solitary and sensual.’ And there’s no doubt that Zhu Jia has an extremely sensual approach to painting, capturing the light, for example, as it bounces off flesh, the pinkish hue of the onset of sunburn, or the lush greens of London’s gardens, both private and public, and seemingly always verdant however grey the skies. There’s always a sense of alienation, that the artist is a stranger in a strange land, whether it comes about as a result of anxiety caused by the invisible barriers of language and culture, or, more fundamentally that Zhu Jia’s true language is visual (as demonstrated by his painting) rather than verbal is something about which we are left to guess. And yet there’s also a sense of optimism here. Despite the sense of awkwardness and alienation, painting after painting, picnic after picnic, conversation after conversation, Zhu Jia continues to turn up.

某种程度上,艺术家的位置恰似法国作家阿尔⻉·加缪1942 年的小说《局外人》的主人公莫尔索——“他是他所在社会的局外人,孤独地、感性地生存在边缘”。毫无疑问,朱加的绘画路径是极其感性的,例如他对光线的捕捉:日光在肌肤上的反射,晒斑附近的粉红色晕,或是伦敦公园葱郁的绿,私密的或公共的,总是那么鲜活,无论天空多么灰暗。又总是存在一些疏离感,艺术家是一个生活在陌生国度的异乡人,疏离感或因语言和文化的无形障碍而生?或者更本质上,朱加真正的语言(如其绘画所揭示)是视觉的而非言语的?然而在还存在一种乐观主义——在窘境感与疏离感之外,有的是一幅接着一幅的画作、一次接着一次的野餐、一场接着一场的对话,朱加持续出现。

朱加 Zhu Jia | 红格子的毯子 Red Grid Blanket | 布上油画 Oil on canvas | 205(H)*200(W)*5cm | 2018

During the eighteenth century, in Britain, a particular genre of painting evolved: the ‘conversation piece’. Such paintings, a form of informal group portraiture, depicted families or genteel society engaged in discussion — perhaps about science, art, politics or the social scene in general, only the props and scenery the surround them, or your knowledge of the people depicted give you clues as to that. As a viewer, you were being invited to be a part of a private moment, a private space, a guest granted entry into an exclusive members’ club, where great matters were being discussed over a picnic or a cup of tea. And yet you were always excluded, outside the frame of discourse. Literally. You were being invited into discussion in which you were mute. An especially British (and often class-based) form of ‘generosity’. Zhu Jia’s current paintings, the majority painted in London, add a new twist to this with the artist as excluded as the viewer, glancing at us, as if in solidarity, inviting us to be present too, all the while knowing that we remain outside. Though, that’s not to say that the artist knew of, or was influenced by this genre. More that some aspects of sociability, despite circumstances and appearances, never change. Or that Zhu Jia fits his current home, London, better than he thinks.

在十八世纪的英国诞生过一个特殊的绘画流派:“对话派”,这种非正式的群像绘画形式描写家庭或上流社会的交谈场面——大致是关于科学、艺术、政治或社会场景的交谈, 观众只能从人物周围的道具和景观、或是凭借对所描绘人物 的了解来猜测谈话的主题。作为一名观看者,你被邀请进入这个私人时刻和私人空间,你是一名被准入私人会员俱乐部的宾客,在那里,人们一边野餐或饮茶一边讨论重大问题。 然而你又总是被排除在那个话语框架之外的——你受邀进入了一场讨论,但你是无声的。这是一种英国式的且通常是某个阶级特有的“慷慨”。如今朱加在伦敦创作的绘画为这一流派加入了一些薪火——艺术家本人与观众一样被排除在外,他孤独地凝视着我们,邀请我们一同加入,同时他始终清楚我们身处局外。并不是说艺术家知道这个流派或受到其影响,而是,尽管环境和呈现在不断变化,社交性的某些方面始终没有改变。或者,朱加比他自认为的更适应他如今的家,伦敦。

©文章版权归属原创作者,如有侵权请后台联系删除