![]()

|

「米修米修收到信号了吗」展览现场 Horizons: Is there anybody out there? Installation view Part 5&6 Words by curator Robin Peckham |

Exhibition Period | 展览时间

2023.9.16 – 10.21

Exhibition Address | 展览地点

天线空间 AntennaSpace

上海市莫干山路 50 号 17 号楼 202 室

Room 202, Building 17, No.50 Moganshan Rd. Shanghai

05

建筑、景观、记忆

Architecture, Landscape, Memory

穿过这些恰好占据展览承上启下中间层的仪式空间,我们稍作休息,在此对建筑和场所进行冥想。展览的这一章节所在的展厅,恰好是在画廊空间和其邻居的过渡地带,也适合让我们思考建筑如何作为身体发挥作用:建筑如何以建构以及回收再利用的方式,来建构多层意义。在当代艺术的某些角落,建筑的视觉感性已经成为客观性和理性的代表,大致而言有种与当前日记式肖像的流行打对台的趋势,而在这一章节中,艺术家们以隐喻和经验的角度来呈现建筑与身体之间的关系,从而让前述打对台的关系变得更为复杂。建筑拥有自己的生命,它们吸收记忆,并将记忆再现为与人类生活的动态轨迹永远交织在一起的纪念碑。

Passing through these ritual thresholds, we pause for a meditation on architecture and place. This chapter of the exhibition, built into the liminal space between the gallery and its neighbor, is a fitting place to think through how buildings function as bodies, collecting and shedding layers of meaning through use and reuse. In some corners of contemporary art the visual sensibility of the architectonic has become a stand in for objectivity and rationality, in some simplistic sense opposed to the ongoing surge in diaristic figuration, and this group of artists complicates this dualism by presenting the relationship between architecture and the body as one of metaphor and experience. Buildings take on lives of their own, absorbing the memories and representing them as memorials constantly intertwined with the more fluid paths of human lives that thread through and between them.

「米修米修收到信号了吗」展览现场

| 在这里,我们可以看到一幅已故艺术家麦志雄的油画,这是他于1990年代中期创作的“风景”系列之一。有趣的是,他还同时创作了“机械”系列,两者间的差异微乎其微:它们都以等轴透视描绘了直线性的结构,从而有种通用的现代主义和技术性质,换言之,建筑物被视为是打造居家生活的机器。艺术家也将它们以难以协调的两种几乎算是对比色的颜料,外加第三种颜色来绘制图解,要么是前两色的灰阶混合,要么是择一使用灰阶色,从而产生了阴影般的形式,仿佛有种在画面色域内退后的感觉。从今天看来,这些绘画很有活力,且令人困惑,显然超前于他们的时代,但比起80年代末以来的杭州和东北艺术家所开创的“理性绘画”相结合。这些绘画尚未被广泛展示或展出,但它们在过去几十年里一直在策展人、收藏家和艺术家的回忆中得到讨论,这是一个适当的环境,适合这种不确定的画作。 |

We find a canvas by the late Mai Zhixiong, one of a series of “Landscapes” that he painted in the mid-1990s. Interestingly, there is also a series of “Machinery” painted in parallel, and the differences between them are marginal: both take isometric perspectives on largely rectilinear structures of a generically modernist and technological nature – buildings are machines for living in – and diagram them in bracingly awkward palettes of two nearly contrasting colors plus a third color that is either a grayed mixture of the first two or a grayed iteration of one of them, resulting in shadowy forms that seem to recede into their fields. Looking at them today these paintings are dynamic and confusing, clearly ahead of their time but tied in with the “rational painting” pioneered by artists in Hangzhou and the northeast since the late 1980s. Not yet widely seen or exhibited, these paintings are discussed in recollections and remembrances of a network of curators, collectors, and artists who have encountered them in the intervening decades, an appropriate milieu for such indeterminate pictures.

Mai Zhixiong 麦志雄

Landscape Series D 风景系列 D, 1995

Acrylic and pencil on canvas

布面丙烯,铅笔

200 x 175 cm

| 乍一看,崔洁似乎在精神上继承了这一传统,她的作品用一种冷静而淡定的手法绘制建筑以及城市雕塑。然而,她并没有选择去描绘模糊的过往残影,相反,她着重分析了我们今日生活审美的历史原因,特别是从集体主义转轨到市场经济初期萌芽的复古未来主义的建筑形式。在《曹杨新村》(2021)中,她描绘了上世纪50年代初建造的曹杨新村,也是新中国在科学社会主义蜜月期内首个“工人新村”。在这里,建筑物仿佛褪色记忆,灰濛濛的,仿佛透过一层窗纱观看,再衬上一座显眼的亮彩色雕塑,呈现两名年轻女性伸手朝天空庆祝的姿态。对于那代人的生活经历而言,这样的景象凝结了童年环境,而这样的雕塑记忆既代表了过往年代的乐观主义,随着它逐渐成为我们当下的一部分,也代表了某种平凡。 |

Cui Jie might appear at first glance as a spiritual heir to this tradition, painting buildings and, in particular, public sculpture with a hand that is cool and collected. Rather than vague shadows of past encounters, however, Cui focuses analytically on the histories and decisions that have contributed to the aesthetic environment that we live in today, drawn in particular to retro-futuristic forms and structures built between the era of collectivism and the early years of the market economy. In Caoyang New Village (2021) she depicts the titular neighborhood, a planned community constructed in the early 1950s, the heady and optimistic first years of scientific socialism in New China, as the country's first “worker's village” intended to comfortably house factory workers. Here the architecture is as gray and sketchy as a faded memory, seen as through a window screen, punctuated prominently by a brightly colored sculpture of two young women reaching for the sky in celebration. Drawing on the lived experience of a generation for whom environments like these recall the comforts of childhood, the memory of a sculpture like this one stands in for the optimism of a past era, and the banality with which it becomes a piece of our present.

Cui Jie 崔洁

Caoyang New Village 曹杨新村 , 2021

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas

布面丙烯和喷漆

200 x 160 cm

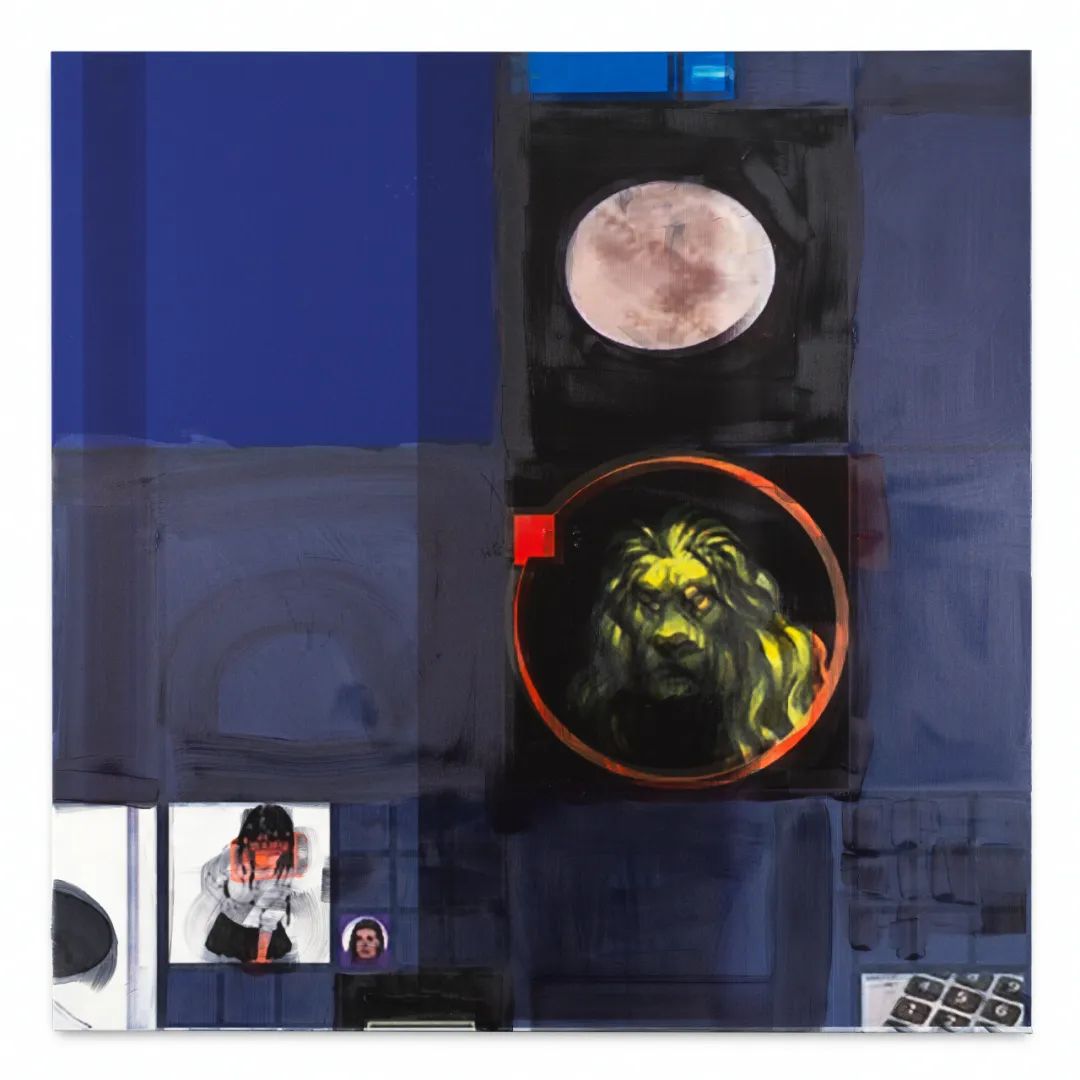

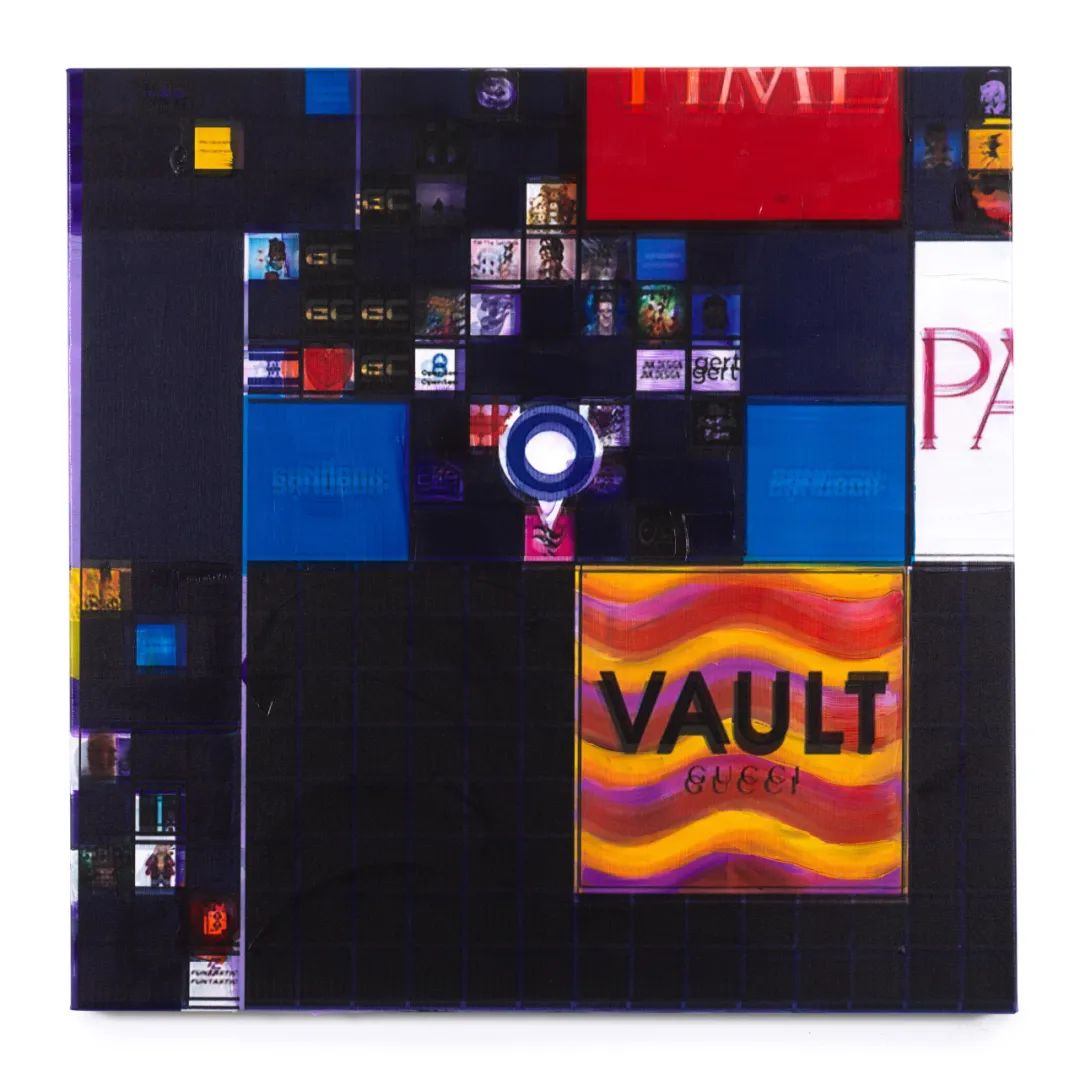

| 再次像是穿越一个岩心样本的层层叠叠,揭示出这个建筑空间不太可能的地形,我们遇到了Simon Denny的“元宇宙景观”系列作品。在过去的几年里,随着对虚拟空间和数字资产的关注,他对虚拟世界中的领土和所有权概念产生了浓厚的兴趣,并思考这些概念如何用我们熟悉的视觉语言来表达。对于那些较为了解Denny围绕在数字生活实践的人们而言,可能会对他在这里展出绘画而感到疑惑;当然,答案是,这些图片需要被理解为地景——有什么比风景画更适合用来思考地景与这一代产权持有人(就像探险家、殖民者、边疆人和浪漫主义者之前的人)的关系?Denny将绘画视为视觉化无形交易的方式,每块画布都标志着特定虚拟世界中特定片段的视图,充斥着该领土内各个地块所有者的标志和形象;而所有这些易变的事物,都在更慢的时间节奏中度过的制作、运输和观看绘画过程中,发生了变化。 |

Moving again as if through the layers of a core sample revealing the unlikely topology of this architectural space, we encounter a series of works from Simon Denny's “Metaverse Landscape” series. Over the past few years, with the turn towards virtual spaces and digital assets, he has become fascinated with concepts of territory and ownership in virtual worlds, and with how these things might be represented in the visual languages with which we are familiar. For those who know Denny best for his profound engagement with the stuff of digital life, it may raise questions to find him represented here with paintings; the answer, of course, is that these pictures need to be understood as landscapes – and what better genre than landscape painting to think through how a generation of property owners (like the explorers, colonists, frontiersmen, and Romantics before them) relate to the landscape? Denny takes to painting as a way to represent supposedly immaterial transactions in a physical form, each canvas marking a view of a particular slice of a particular virtual world, replete with the logos and imagery of the various owners of tracts within that territory, all mutable things that have no doubt shifted over the course of the slower time scale it takes to make and ship and view a painting.

Simon Denny 西蒙·丹尼

Metaverse Landscape 34: The Sandbox LAND (-108, -158)

元宇宙景观 34: 沙盒乐园(-108、-158), 2023

Oil on canvas, UV print, Ethereum paper wallet, dynamic ERC-721 NFT 布面油彩、UV印刷、以太坊纸制钱包、动态 ERC721 NFT

200 x 200 cm

Simon Denny 西蒙·丹尼

Metaverse Landscape 41: The Sandbox LAND (-1, -36)

元宇宙景观 41: 沙盒乐园 (-1、-36), 2023

Oil on canvas, UV print, Ethereum paper wallet, dynamic ERC-721 NFT 布面油彩、UV印刷、以太坊纸制钱包、动态 ERC721 NFT

100 x 100cm

「米修米修收到信号了吗」展览现场

|

此刻,Dora Budor的作品《Autophone (Bull)》(2022)看上去非常眼熟,它是一个充满机械气息的机器,可能是工程或建筑模型。它们确实是建筑组件,她将配对组件的性别化系统中(如螺栓和螺母,或电插头和插座)属于“公”的组件做了稍微抽象的调整。Budor使用了专门制作乐器的乐器木来重构这些组件,并在这些新混合体内部放置一根根震动棒。在这里,艺术家通过将身体插入建筑内部,从而将建筑变成了一个身体;这一切都是来回不断的,不停的振动,但整个配置的美妙之处在于它们都没有功能或目的。它们在倾听自身,在这里,它们只为了自己的愉悦而存在。 |

By this point Dora Budor's Autophone (Bull) (2022) looks very familiar, a machine-flavored machine that could be a draftsman's model or an architect's maquette. As it happens, they are indeed architectural components: slightly abstracted versions of the pieces that would be labeled “male” in the gendered system of paired fasteners (like a bolt and a nut, or an electrical plug and outlet). Budor recreates these forms out of a material called tonewood, a category of woods used in the production of musical instruments, and sets vibrating sex toys into the bodies of these new hybrids. Here the artist makes the building into a body by inserting a body into a building inside of a body in a building; it's all a lot of back and forth, a lot of ceaseless vibration, but what's beautiful about this whole configuration is the fact that none of it has a function or purpose. It's listening to itself, and it's here for its own pleasure.

Dora Budor 朵拉·布多

Autophone (Bull) 自鸣乐器 ( 公牛 ), 2022

Tonewood, steel, sex toys, electronics

琴音木,钢,性玩具,电子器件

25 x 42 x 38 cm

| 李明参展的绘画全以神秘的标题“2014201620212022”命名。这些画色彩丰富,而其中仿佛是血做的感光图的印痕,则是源于塑料打火机的爆炸,最初源于李明早在2014年开始的一系列技术不太娴熟的投掷打火机燃烧纸张的行为作品。他的视频作品《361》(2014)则记录了艺术家在黑暗中将361个打火机砸在一张纸上的过程。除了这个行为的暴力唤醒外,李明之所以转向这些廉价的一次性打火机,主要是出于社会学的原因:他来自湖南,那里是这些打火机供应链的主要枢纽,它们的普遍存在使得打火机的制造和消费成为一个独特的对称过程。但最先引起他注意的是上面印的苹果图像——一家打火机供应商,在他们的一系列打火机上印有最新款iPhone型号的名称,以及山寨的苹果标志。如果将这些高端和低端的消费品版本统一起来(而高低端两者的供应链在地理及文化距离上可能并不遥远),我们就会陷入现代社会的关键问题——成瘾。 |

Paintings by Li Ming, all cryptically titled “2014201620212022”. These richly colored canvases, like photograms made in blood, are remnants of the explosions of plastic lighters, outgrowths of a less technically proficient series of lighters thrown at paper that Li began as early as 2014; the video 361 (2014) documents the artist breaking the titular number of lighters against a sheet of paper in the dark. Aside from the violent invocations of this action, Li Ming has turned to these cheap disposable lighters for largely sociological reasons: Hunan, where he is from, is home to the main hub of their supply chain, and their ubiquity makes their manufacturing and consumption a uniquely symmetrical process. But what first caught his eye was the Pingguo brand, a lighter vendor who printed the name of the newest model of the iPhone along with a shanzhai Apple logo on successive generations of their lighters. Uniting these high- and low-end versions of consumer products across supply chains that, geographically and culturally, can't be that far from one another, we land on the crux of modern society – addiction.

「米修米修收到信号了吗」展览现场

Li Ming 李明

2014201620212022 No.2, 2023

Disposable lighter exploded on handmade watercolor paper, Epson UV print, mounted in aluminum frame 一次性打火机爆炸于手工水彩纸上,爱普生UV微喷,金属铝框装裱

125 x 220 cm

| 虽然从远处看,Alexandra Noel的所有展览看起来都一样,因为她的作品总是由一系列小型绘画组成,以相同的高度和间隔挂在展场空间中。但尽管这些展览看来相似,每一幅绘画却都不同。我想,这是因为建筑空间有能力在观众漫步其中时,吸收并介入我们的生命。她的每幅绘画都坚持将自身作为对象,我们最好注意它们的个别性,而不是视之为构成整体的局部。当这些作品被放到一起去时,它们并不是组成完整语言的一个个元素,而更像是是一道道被打散了的梦幻剧目,留给尚未到达现场的人重新推敲当初的顺序。《A Painting as Big as a Calendar (I must have been 9)》(2023)使我们惊叹于它以有限细节撑起构图的套娃,然后通过玩弄阴影,将我们从画布表面拉开,再将我们推回到画布表面。《Holding Up the Sky》(2023)则呈现建筑之上的建筑,似有若无地说着50年代中国女性主义以及阳具纪念碑式的玩笑,但它也让我们坠入色彩的研究之中,并且迅速收尾。《Fly Swatters (Positive and Negative)》(2023)和《Bookmarks》(2023)则非常享受绘画的过程,摆弄着绘画如何在墙上呈现,以及事物转变为绘画后,其功能性的转变。最后,《Stay Safe》(2023)进一步让我们怀疑我们的感官,看了一眼又再回头,想用指尖检查作品的肌理,因为在这件作品中,我们看到石头表面嵌入了一颗珍珠,从而让我们不知道绘画在哪里,或者,这张作品根本不算是绘画。 |

From a distance all of Alexandra Noel's exhibitions look the same, because the format invariably consists of a series of diminutive paintings hung at the same height at equal intervals around a gallery space. But although the exhibitions look the same, every single painting is different, and I think this says something about the capacity of the architectural volume to absorb and engage with the lives of viewers like us as we wander through them. Each painting insists on itself as an object, and we would do well to pay attention to them individually rather than as part of a project. Together they constitute not the elements of a language but the lines of some oneiric play, left chaotically to be reordered by someone yet to arrive at the scene. A Painting as Big as a Calendar (I must have been 9) (2023) has us marveling at the level of finite detail that goes into a composition within a composition, then startles us with a play of shadows that pulls us away from and then smushes us back down onto the surface of the canvas. Holding Up the Sky (2023) quotes architecture on architecture, with or without a joke about 1950s Chinese feminism and phallic monumentality, but it also leaves us lost in a color study that ends all too quickly. Fly Swatters (Positive and Negative) (2023) and Bookmarks (2023) take joy in the process of painting, toying with how the work sits on the wall and with the unmoored functionality of the object depicted after it is turned into painting. Stay Safe (2023), finally, has us doubting our senses, turning back to run our fingertips over the other works to check their textures, because here we have a pearl inserted into a stone surface, and we're left wondering where the painting is, or if there was ever painting here at all.

「米修米修收到信号了吗」展览现场

Alexandra Noel 亚历桑德拉·诺艾尔

Holding Up the Sky 撑起苍穹 , 2023

Oil and enamel on wood panel

木板上油彩与珐琅漆

15.3 x 10.2 x 1.9 cm

Alexandra Noel 亚历桑德拉·诺艾尔

Trickle Down 涓滴, 2023

Oil and enamel on wood panel

木板上油彩与珐琅漆

15.2 x 15.2 x 1.9 cm

06

上海羊皮纸

Shanghai Palimpsest

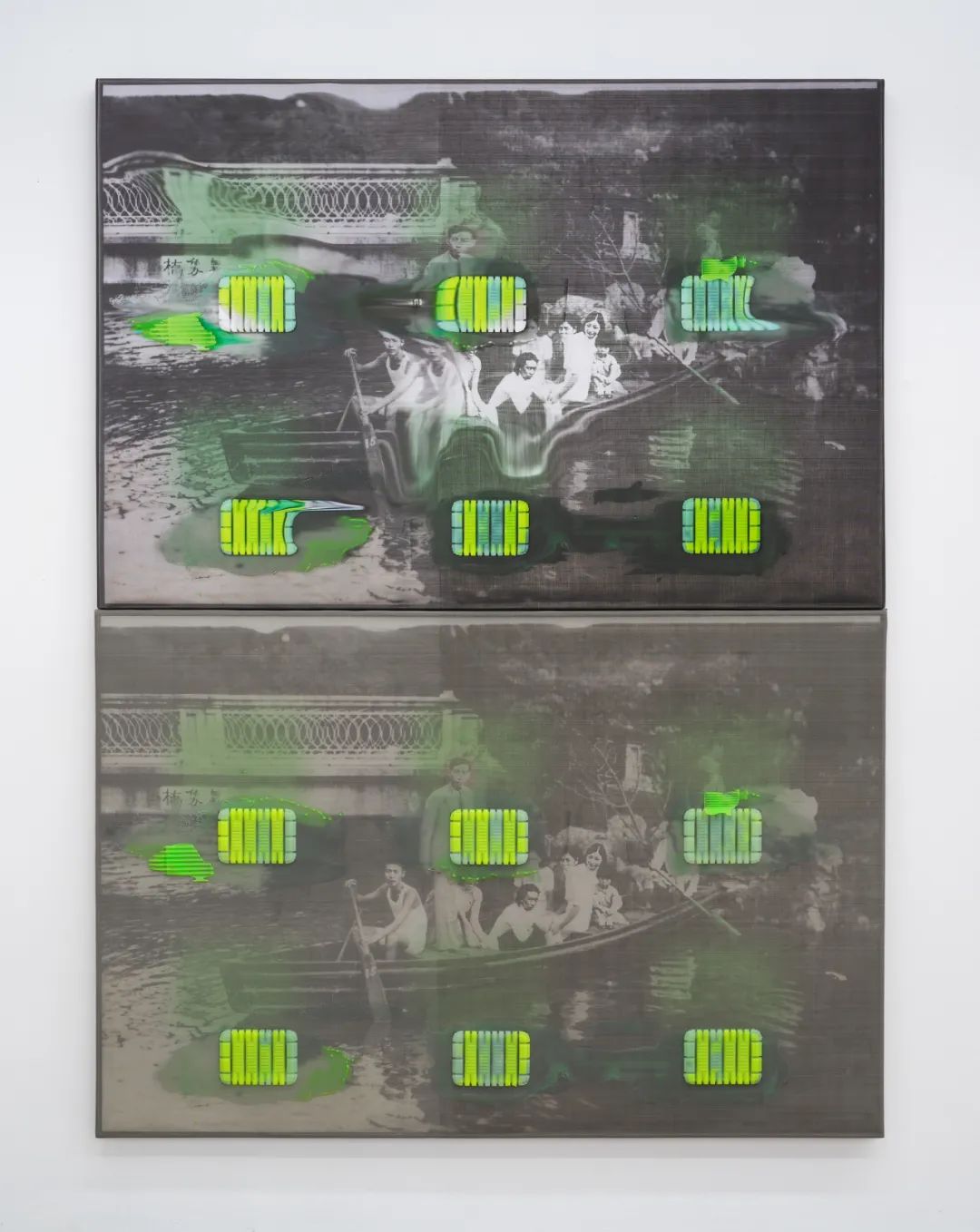

在这个展厅的核心地带,我们搭建了一座临时建筑,用于展示徐梯善的一系列作品。在这个专门为这四幅画搭建的空间中,每个墙面挂了一幅作品,其建筑形式则塑造了外围更大房间中关于具身记忆和空间的对话。这些绘画标志着徐梯善首次认识他的家族当初在上海的历史,他后来也在纽约和香港的一系列作品中进一步展开(分别是睽违32年后的首场纽约画廊个展以及他首度的亚洲个展)。然而,作为材料的初步实验,这些作品在上海一直未被展示;其中五幅中有四幅作品从未离开上海,而其中一幅则前往了马尼拉。我很高兴首次在这里展示这些作品,因为它们在艺术家作品演变中占据了一个切线,我认为这重新激发了他创作的激情,特别是因为它们以如此精确的特定性来处理地方。同样是上海,生于80年代初的崔洁,从社会主义时代寻找当今时而短缺的共通价值观,而50年代生的徐梯善则回忆起30年代上海这样一个被遗忘的民国时期。

At the heart of this room, we have constructed a piece of temporary architecture, a supplement to the building that houses a cycle of works by Tishan Hsu. This room was built specifically for these four paintings, a wall for each, and its architecture shapes the conversation around embodied memory and space taking place in the larger room around it. These paintings mark Hsu's initial engagement with his family's history in Shanghai, a story that he later elaborated further in a body of works exhibited in New York and Hong Kong (these were, respectively, his first New York gallery show in 32 years and his first Asian solo show). As rougher experiments with the material, however, these works remained out of view in Shanghai; four out of five paintings have never left the city, while one made its way to Manila. I am excited to present them here for the first time because of the tangent they occupy within the evolution of the artist's work, one that I understand as central to the reinvigorated excitement around his practice, and, particularly, because of the way they deal with place in such exquisite specificity. Where Cui Jie, born in Shanghai in the early 1980s, looks to the socialist era for its embrace of shared values that sometimes seem in short supply, Tishan Hsu, born in Boston in the early 1950s, recalls a forgotten slice of Republican-era Shanghai from the 1930s, a time and place his family lived through but that he himself never knew.

「米修米修收到信号了吗」展览现场

要沿着这条时间线向后追溯,我们可以从位于今日上海市区西北角曹杨新村出发,上内环,向东北行驶十多公里,从复旦大学附近下交流道。这里是中国知识分子活动的关键地带,也是学生体验城市生活的中心,我们来到了上海肺科医院,外观与任何一家市区三甲医院没什么不同。然而,在主楼后面藏有一个美丽而小巧的公园,叶家花园。一条环形水道环抱,并散落着几座亭子和其他建筑物,有传统的露天风格,有玻璃窗加尖顶的独特洋泾浜装饰风,还有一座更大的白色欧式建筑。我们之所以在此,是因为这是徐梯善一组作品的核心中的景色,但他只是简单将其命名为“划船场景”。原始照片中,位于中心位置的人物是钱歌川(在徐梯善的重新创作中,由于周围的人物更加引人注目,所以这个人物变得模糊暗淡),也是艺术家的舅爷,拍照者可能是钱歌川的哥哥钱慕韩——肺科医院前身澄衷疗养院在草创时期的副院长。这家医院的成立,还要归功于邻近的万国体育会创始人叶贻铨捐赠政府的土地,据闻,叶贻铨的父亲拾金不昧,将捡到的行李箱还给一位美国商人,从而获得他的投资并因此致富。在这张照片拍摄后没多久,战争就来到上海,空袭也摧毁了万国体育会的赛马场,不过,医院和花园则幸存下来。

To follow this axis backwards in time we might set out from Caoyang New Village, located in the northwest of contemporary Shanghai, and get on the Inner Ring highway, heading northeast for just over ten kilometers or so. Exiting around Fudan University, a major hub of Chinese intellectual life and the epicenter of the student experience in the city, we would find ourselves at Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital, a highly regarded facility that looks like any other major urban hospital. Tucked behind the main building, however, there is a lovely if small park known as the Ye Family Garden, a ringed waterway marked by several pavilions and other buildings, some in the traditional open-air style, one in a distinct hybrid Art Deco style with glass windows and a more steeply pitched roof, and one a larger white structure of a fully European design. We are here because this is the site of a photograph at the heart of Hsu's body of work that he has titled simply Boating Scene. The figure at the center of the original picture (blurred and darkened so that the surrounding figures attract more attention in Hsu's reworking) is Chien Gochuen, the artist's great-uncle, presumably photographed by his brother Dr. Qian Moo-Han (Chien Moo-Han), the first superintendent of the hospital then newly constructed on land donated to the government by T.U. Yih, founder of the neighboring racecourse and heir to a fortune that, according to anecdote, got its start when Yih's father returned a lost piece of luggage to an American businessman who was moved to invest in the young man's ventures. When war came to Shanghai a few short years after this photograph was taken, the racecourse was destroyed in the bombing, but the hospital (and the garden) survived.

| 不过,还是到了2012年之后,徐梯善的母亲身后留下的一系列信件和相册使徐梯善起心动念追溯这段历史,并从2013年到2016年旅居上海,住在他素未谋面的父系亲戚家中。初见钱慕韩的后代,让徐梯善感到非常震动的是他们的家族相册。起初,他的动机是寻找家庭相册略去的缺口,那些特定的照片,或者页面损坏甚至完全丢失的地方,以及其母亲因移民和迁居的个人创伤而被压抑的口述历史中的空白。徐梯善运用过去二十年来在他的作品中使用过的数字编辑工具处理这些相册的残片——扫描、添加滤镜、扭曲和复制;这些实验结果便是在这里展出的作品。所有作品都用了敷上彩色硅胶的灰度数字打印画布。《Boating Scene – Green》(2014)将上述照片打印两次叠放,图像被扭曲、抹除,每张图上都有六道荧光绿色硅胶的痕迹,有点像是攀岩手把或运动鞋鞋底。《QMH – Bucket Bottoms》(2014)切换到了家庭相册中的其他照片,各种各样的独照或家族照,包括了来自实际相册的纸张和胶水痕迹。这里的二乘四的硅胶网格看起来像是油漆桶剩料上的一系列标记。《QMH – Double Ring-Doubled》(2014)用不同的照片重复了相同构图,在此更大却更稀疏的硅胶环,看起来有点像划船场景中,人行桥上挂着的红白色救生圈。《QMH – Missing Photos》(2015)用照片网格本身来关注哪些照片还在,哪些已经遗失了;恰当地说,这里少的一件作品有某种伴随性质:《QMH – Dread – Fog》(2014)在灰度照片的网格上插入了一层漂浮的椭圆形污点。这最后一件作品曾在2019年香港Empty画廊的个展“刪”展出,而此处其他四件作品中的构图时刻,在进一步放大、拉伸、捏合和扭曲中,也成为了那个展览中的其他作品。另一件“QMH”作品和一件已经被毁坏得无法辨认为图像的“划船场景”系列作品,也在2021年在纽约Miguel Abreu 画廊的展览“皮肤-屏幕-草地”中展出,从而将这段旅居上海,极度个人的经历,消化和重组成徐梯善现今工作室创作的原材料。 |

It was after 2012, when his mother passed away leaving a series of letters, that Hsu became interested in tracing this family history and decided to spend 2013-2016 living and working in Shanghai, living with relatives on his father's side who he had never previously met. Visiting the children of Dr. Qian for the first time, he was struck by the historical photo albums in their home. He was motivated, at first, by the ellipses and lacunae that he found in these family albums, places where particular photographs or pages were damaged or missing entirely, as well as gaps in the oral histories shared by his mother, suppressed by the personal traumas of migration and relocation. Hsu worked with the remnants of these albums, treating them with the digital editing tools that he has used in his work for the past two decades – scanning, adding physical filters, warping, and doubling; these experiments resulted in the works exhibited here. All take the form of grayscale digital prints on canvas overlaid with pigmented silicone. Boating Scene – Green (2014) prints the photograph described above as a morphed digital copy. The images are warbled and wiped, each one hosting six moments of neon green silicone interventions cast from the plastic trays containing meat in Shanghai supermarkets, geometries in which Hsu saw references to silicone chips. In juxtaposing the actual and the digital in these works, Hsu sees how the synthetic image retains the full intensity of the original, creating a hybrid reality of both, a doubling that echoes his experience of his own family history, first through the virtuality of photographs and information accessed through the web of family members in the diaspora, and then again in person. QMH – Bucket Bottoms (2014) switches to other photographs from the family albums, variously picturing single subjects or formally posed groups, with traces of paper and glue effects from the physical albums included, too. Here the grid of two-by-four silicone elements is cast from the bottoms of buckets sold on the Shanghai streets Hsu passed on his way to the studio every day. QMH – Double Ring-Doubled (2014) repeats the same composition with different photographs, and with the silicone rings now larger and fewer, looking something like the red-and-white life rings we might imagine hanging on the pedestrian bridge of the boating scene. Through photography Hsu enacts a liquid change to the formal level of the work, so that the digital version floats above the original. It was only years after producing the work that the artists learned that his maternal great-grandfather's company, founded in Hunan a century ago, was named Double Ring. QMH – Missing Photos (2015) concentrates on the grid of photographs, on how many are still there and on how many are missing; appropriately, the work that is absent here is something of a companion piece: QMH Dread-Fog (2014) inserts a layer of floating ovoid stains over the grid of grayscale photographs beneath. This last work was shown in the 2019 exhibition “delete” at Empty Gallery in Hong Kong, while compositional moments from the other four pieces here grew into the other works in that show, often further zoomed, stretched, pinched, and warbled. Another “QMH” work and a “Boating Scene” work, this last corrupted beyond recognition as an image, were included in the 2021 exhibition “skin-screen-grass” at Miguel Abreu Gallery in New York, completing the cycle by digesting and reassembling this intensely personal experience in Shanghai into raw materials for Hsu's ongoing studio practice.

Tishan Hsu 徐梯善

Boating Scene – Green 泛舟之景 – 绿, 2014

Digital print on canvas, silicone on stainless steel wirecloth, wood stretchers

布面数字印刷,不锈钢丝布上硅胶,木担架

121.9 x 177.8 x 7.6 cm x 2 (diptych 双联画 )

Tishan Hsu 徐梯善

QMH – Double Ring-Doubled QMH – 双环 – 双倍, 2014

Digital print on canvas, silicone on stainless steel wirecloth, wood stretchers

布面数字印刷,不锈钢丝布上硅胶,木担架

96.5 x 134.6 x 7.6 cm x 2 (diptych 双联画)

回顾徐梯善在1980至90年代创作的作品,以一种后见之明,我们可以轻松地看到他的审美、物质性和哲学兴趣既是其自身年代的产物(赛博朋克、身体恐怖小说、贱斥),又在预见到我们的消费技术和身体如何通过屏幕、特效、镜头、医疗干预、滤镜和其他修辞手段相互构成的方式上具有显著的预见性。所有这些作品所表达的是今天的媒介身体体验;将个人身体抽象化几乎是一种普遍经验。然而,在这一系列的上海作品中,我们发现了一些不同寻常的东西——一个如今存在于所有艺术家作品核心的人道主义主体的诞生。看起来,他自己的具体历史经验就像跳板:记忆成为即将到来的一切的构架,为艺术家在可能会压倒我们中的任何一个人的身体、媒体和技术的宇宙中预留了一个位置。徐梯善为我们提供了一个支点,就在这个上海北郊的园林医院中。

Looking back on Tishan Hsu's body of work produced throughout the 1980s and 1990s with the benefit of hindsight, it's easy to see his aesthetic, his materiality, his philosophical interests as both fully of their own moment (cyberpunk, body horror, abjection) and remarkably prescient in their anticipation of the ways in which our consumer technologies and our bodies would come to co-constitute one another through screens, special effects, lenses, medical interventions, filters, and other rhetorical devices. What all of this work speaks to is the experience of the mediated body today; it is a nearly universal experience that abstracts the individual body. What we find in this cycle of Shanghai works, however, is something a bit different – the calling into being of a humanist subject that now resides at the heart of all of the artist's work. The specificity of his own experience of history reads like a springboard: memory becomes the architecture of everything else that is to come, reserving a space for the artist within the cosmos of body, media, and technology that can threaten to overwhelm any given one of us. Grounding us in this garden-turned-hospital in the northern reaches of Shanghai, Hsu hands us a leg to stand on.

「米修米修收到信号了吗」展览现场

文字翻译:陈玺安

图片致谢艺术家及天线空间

摄影:Cra

©文章版权归属原创作者,如有侵权请后台联系删除